Suppose after a night of rather heavy drinking at a bar, I say to one of my friends “There were at least two dozen kamikazes in the bar last night!” As it happens, she was also at the bar last night, although not with me, and she disputes my claim, on the ground that there were no Japanese aerial suicide pilots in the bar, and “kamikaze” means “Japanese aerial suicide pilot.”

I explain that identical or similar words can have different meanings, and that a “kamikaze” is also a drink consisting of equal parts vodka, triple sec and lime juice. I explain to her I am talking about the cocktail, not the Japanese suicide bomber pilots. I further explain that I happen to be in privileged position with respect to my claim to know what it is that I am talking about.

She rejects this, insisting that “kamikaze” means “Japanese aerial suicide pilot” and nothing else, neither the common usage of the word among cocktail drinkers nor my usage of the word to mean a drink notwithstanding. On this basis, she continues to insist that my claim about there “being at least two dozen kamikazes in the bar last night” is false.

What should we make of this argument on her part?

It seems obvious that it is a very bad argument, because she is failing to address my claim at all. Her objection is an appeal to a different sense of the word that has no relevant connection to my use of the word. I recognize there is a very tenuous historical connection between the name of the drink and the Japanese aerial suicide bombers, but it likely isn’t anything more than someone at some point thinking “that would be a cool name for a drink.”¹

Consider also the names of various American car models: “Bronco” “Accent” “Caprice” “Passport” “Suburban” etc. Like my kamikaze example, it would seem merely fatuous to claim that the owner of a Hyundai Accent does not have an accent, because an accent means “a distinctive mode of pronunciation of a language, especially one associated with a particular nation, locality, or social class.” So it does, but it also means “a distinct emphasis given to a syllable or word in speech by stress or pitch” and “a car model produced by Hyundai.”

Very obviously, if a person attempts to refute your argument or claim on the basis of a sense of a word which you don’t mean, they are simply committing a fallacy of equivocation. Equivocation is possible only because identical or similar words can and do have multiple senses, sometimes related, sometimes not.

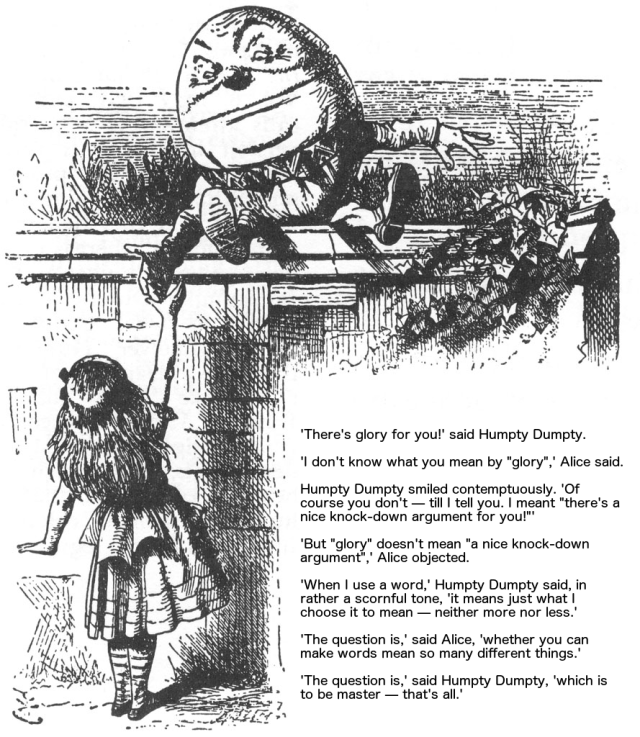

Let’s take a third case and be as blatant as possible. I claim “Water is H₂O.” My opponent is a Humpty-Dumptyist who simply stipulates that he defines “water” as “lead.” He then argues that lead is not H₂O but Pb, and therefore I am wrong. Has he refuted me? Obviously not. But why not? Because when I said “water” I meant “water” and not “lead.” My claim is about water. His refutation required him to pretend my claim is not about water but about lead, which it isn’t.

So what’s the point? Isn’t it obvious that this move of refuting something other than what a speaker means is fallacious?

It should be obvious, but I find it is very common tactic used by many atheists. When I or other theists make claims about God, the atheists will claim, falsely, that we are making claims about gods. Now, I would not deny there is historical connection between the words “god” and “God” just as there is between “kamikaze” and “kamikaze” or between “accent” and “Accent.” But the words denote very different things. This difference in denotation is in fact the reason “God” is capitalized whereas “god” is not—it is to mark the difference between the concept of “God” and the concept of “a god.”

Not only is this established usage, it is within the rights of the theist to define what he or she is talking about. You can dispute my claim that God exists if you wish to. But you cannot dispute it by claiming that I am talking about something I am not talking about, or claiming something I am not claiming, and refuting the thing I am not claiming and not talking about. Such a “refutation” is no refutation at all, nor does it undermine my claims in any way, since it is simply about something else, which I am not talking about.

So not only does the atheist seem to be confused about the distinction between God and gods, he is actively intellectually dishonest if he insists on redefining terms on the basis of “what they really mean” or (what comes to the same) “what he thinks they should mean.”

It should be obvious that if a person asserts something about something (S is P) that the truth or falsity of the assertion depends on the meaning and definition of the terms, and all else being equal, the one who asserts something has the right to define her terms, since she is in the epistemically privileged position of being the only one who knows what she is talking about.

“You mean something other than what you mean” is never a legitimate argument, since what I mean is both entirely up to me, and known only to me (up until the point at which I define my terms, thereby making it clear what I mean).

Atheistic appeals to gods are fallacies of equivocation when God is the subject at issue.

Who argues like that? Silly people!

LikeLike

People who think it’s clever to say “Do you believe in Odin? Why don’t you believe in Odin? If you can tell me why you don’t believe in Odin, that’s why I don’t believe in your god!”

They get confused when I say “I don’t believe in Odin, because Odin is a god, and I don’t believe in gods because I believe in God.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yea I can see that being asked and your response is perfect logic!

LikeLike

On a more irrelevant note, etymologically speaking, “Kamikaze” is a Japanese word meaning “Divine Wind”, where the root words are “Kami” (“God”) and “Kaze” (“wind”).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, and the original “divine wind” was a perfectly-timed typhoon that destroyed the fleet of Kublai Khan, which would otherwise certainly have conquered Japan.

LikeLike