I wanted to share an interesting thought experiment concerning the nature of time. I’ve known about this for many years, but can’t for the life of me remember the name of the philosopher who came up with it—I’m 99% sure it was a woman, but beyond that I have no clue. If any one knows the origin, please let me know. [UPDATE: Not a woman. It was Sydney Shoemaker, who proposed this thought experiment as a counter to J. M. E. McTaggert’s proposition “There could be no time if nothing changed” — a view held by Aristotle, among others, and a view that I’m more sympathetic too than not—interesting as I find Shoemaker’s thought experiment.]

Anyhow, our unknown philosopher [Sydney Shoemaker] asks us to imagine a universe with some unusual properties. This universe is very much like our own, except that it is divided into three distinct regions, call them A, B, and C.

And each region has a strange property with respect to motion. Every so often, at regular intervals, all motion in a given region stops completely, leaving everything and everyone inside the region completely “frozen” or “suspended.” Anyone in a non-suspended region can easily observe that everyone and everything in a suspended region is completely motionless. Each motion freeze lasts for exactly one year. Those inside the motion frozen region do not experience the freeze subjectively at all. From their perspective, it appears as if the other non-frozen region(s) change totally in an instant (a year’s worth of change).

Region A motion freezes 1 year out of every 3.

Region B motion freezes 1 year out of every 4.

Region C motion freezes 1 year out of every 5.

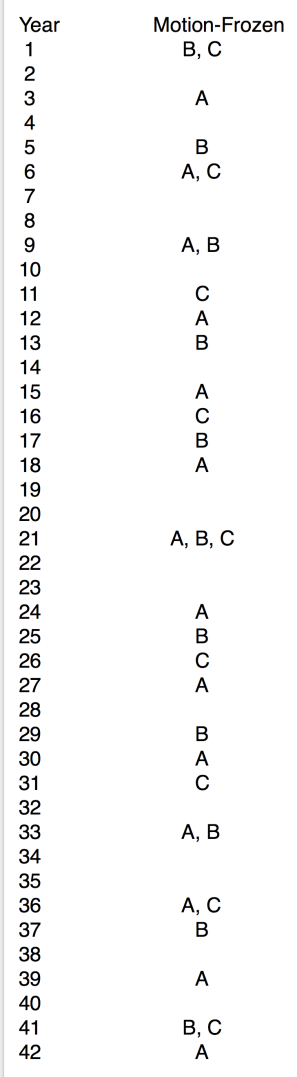

So it looks like this:

So let’s consider what this would look like as the years pass. I have arbitrarily decided to start in a cycle where B and C are both motion-frozen in year 1 and A was frozen in year 0 and so on this chart freezes again in year 3:

It isn’t hard to work out that regions A and B will freeze together once every 12 years (3 x 4), that regions A and C will freeze together once every 15 years (3 x 5) and that regions B and C will freeze together once every 20 years (4 x 5). And it further isn’t hard to work out that all three regions A, B, and C, will freeze together once every 60 years (3 x 4 x 5)—something that happens to happen in the 21st year as I’ve set it up (I can’t be bothered to type out 120+ years—you can see the patterns well enough).

Now, everyone agrees that time in very closely related to motion or change. And indeed, we usually imagine a timestop in fantasy or science fiction as a “freeze” or “suspension” of all motion, just as actually occurs in this universe. And indeed, from the subjective point of view of those in a motion-frozen region in this universe, no time will have been experienced as passing, either subjectively or by external objective phenomena within the region (e.g. no one will have aged in the frozen “year”).

So, here is the question: is time independent of motion, or not?

From the point of view of anyone within a non-frozen region looking at a frozen region in universe ABC, it is clear that “that region is frozen for one year,” so that time passes despite the lack of motion. So they have good reason to think time is independent of motion, at least the motion of the frozen regions.

From the point of view of those in a frozen region, although they experience no passage of time during their “frozen year” they do see that the other regions freeze for one year, and they see that on a regular basis, the other regions they expect to be non-frozen while they are frozen do indeed “leap ahead” by one year. So they have good reason to think time is independent of motion.

What about year 21? Or more generally, the year that occurs every 60 years when regions A, B, and C all freeze? No one at all will experience this freeze, or be able to see it “from outside” since it affects all three regions. There will be absolutely no detectable evidence that it occurred at all.

However, my philosopher whose name I can’t recall [but I now know to be Shoemaker] asks: isn’t the most rational conclusion to hold that all three regions of the universe did, in fact, “freeze for one year” in which time did, in fact, pass—even though with motion suspended this had no effect on anything or anyone? Wouldn’t it be more rational to believe that “one year passed in which nothing happened because everything was frozen” than to believe that otherwise entirely regular and predictable time freeze simply did not occur (when what we would expect is for it to occur in all three regions, and thus expect it to be undetectable)?

One consequence of this would be to hold that year 21 DID NOT HAPPEN, but it this is so, then it would not be true that A freezes every 3 years, B every 4, and C every 5, but that this happens except that, every 60 years, when the freeze would include A, B, and C, no year happens, and A waits 6 years to freeze, B 8, and C 10 years. The principle of parsimony suggests that an ad hoc adjustment require by saying that the “unexperienced by all year” simply did not happen is less rational than simply accepting that there really was a “year experienced by no one,” which is both in line with the rules of this universe and also what we would expect of the 60th year—namely, that it really did happen, but since everyone happened to be frozen, no one experienced it.

But if this is the case, must it not be the case that time—however much we experience by means of and through motion—is yet not motion, but something that can also, theoretically, measure rest or non-motion?

What do you think? Leave some comments. I’m interested if you find this thought experiment enough to motivate an intuition that time really is logically and really distinction from motion or change, however closely connected the two are either ontologically or phenomenologically.

I think it works, but to me the idea that the year did not happen because everyone was frozen seemed bizarre, so perhaps I’m not the best target for this experiment. I thought this related article was interesting –

http://physicstoday.scitation.org/do/10.1063/PT.5.3047/full/

LikeLike

Early scientists would claim there was a 4-year period with no freeze and devise complex models that would be proven wrong once every few decades. Adjustments would be made until some scientist proposes the entire universe is frozen. Like the thought experiment, it would be abstract. There would be websites online claiming the freeze year is a fake, designed by the government to collect more taxes or an insurance company scam. As a practical matter, a total freeze is unknowable except in the abstract. You might have been frozen multiple times, for a total of 5 million years (to God?) before finishing this comment.

LikeLike

I seem to remember Sydney Shoemaker arguing something very like this (against an argument by McTaggart, maybe?) in “Time without Change”. Last time I read it was in graduate school, so I don’t know if he was adapting someone else. And it got a fair amount of discussion at one time, so it could be that you’re thinking of someone else’s version in particular.

I think there are at least two related problems with the scenario:

(1) The set-up already assumes that one can measure years without regard to change. While the point is to detach time and change conceptually, this actually seems to require an explicit account of how the measuring-out of a year is possible without change. (After all, a reason for the durability of the idea that time is dependent on change since Aristotle is that all our actual measurements of time are by clocks — which are changes used as reference points for other changes; so the real need is to give a reason for thinking that time could actually be anything more than a kind of comparison to a change.)

(2) If there is no actual change going on, then it seems impossible to account for the unfreezing — a change requires a cause, which means there has to be something other than the regions that are frozen, to account for the fact that they do regularly unfreeze at specific times. But then, of course, the real question is the nature of this cause and how time relates to it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sydney Shoemaker! That’s it. Thank you.

LikeLike

One thing that sticks out to me is that the argument for time being separable from motion invokes the “principle of parsimony”…which is not in fact a hard rule of reasoning the way that, for instance, the principle of non-contradiction is. It is, rather, merely a heuristic rule of thumb. Furthermore, I’m not entirely convinced that the assumption of an actual “year experienced by none” actually is the most parsimonious. It produces the simpler *mathematical model* compared to the assumption of a skip in the pattern, but it requires the assumption of some *thing* (a missing year) for which there is no shred of observable evidence (aside from that its assumption makes the math nicer), and it requires the assumption of an entirely separate component of reality (“time”) which is distinct from (but somehow influences/interacts with?) motion (as opposed to time and motion being two sides of the same coin). (This further raises the question of what “time” in this system even *is*, beyond simply an abstraction invoked to simplify the math.)

There’s also the issue of time being relative to a frame of reference. When sector A is frozen while B and C remain in motion, B & C see A being frozen for one year…but from A’s perspective, B & C jump forward in time by one year. Can we, in fact, say that one perspective or the other is more “true” or “real”? It’s basically the same issue as that presented by Einstein’s theory of relativity in actual physics. If an astronaut is sent on a journey at a high percentage of the speed of light, he will experience less time passing for him than is passing back on Earth. Is this a case of the astronaut’s time slowing down (as it would be seen from an Earthbound observer’s reference frame), or of the Earth’s speeding up (as it would be seen from the astronaut’s frame)? Or is it only the relative difference between the two that matters, and whether you spin it as one slowing down or the other speeding up is simply a matter of preferred framing?

If it is simply a matter of preferred framing, then there is no difference between a universal freeze and no freeze at all, because there is no *relative* difference. Just like if time in the whole universe was speeding up steadily and uniformly across the whole universe (say, the length of a second decreases by 10% over the course of each year), it would be indistinguishable from a constant and steady flow of time.

(It’s also worth noting that the the *observed* phenomenon of relativistic time dilation is explained precisely on the notion that time and motion are intrinsically linked. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time_dilation#Simple_inference_of_time_dilation_due_to_relative_velocity)

LikeLike

It seems to me that a problem with the thought experiment is the observation part. Since time is frozen for light and air, it should be experienced as the part of the universe going black. Further you couldn’t enter since the moment any of you entered time would be frozen for it and it couldn’t be pushed out of the way so you could keep moving, so the actual experience of it would be that that part of the universe went black and couldn’t be interacted with.

That said, I think that Brandon’s point #2 is very important. There must, as he says, be a cause of this, and therefore change from its perspective, and therefore a way to measure the time passing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose I’m late to the party on this, but I’ve suspected it as well, though I did so considering how there was a change in the contingency of beings, i.e. angels, who exist outside of our time, but are not eternal as God, but only participate in it. Namely, the creation of angels shows there is a difference inbetween motion/change and corporeal time.

LikeLike