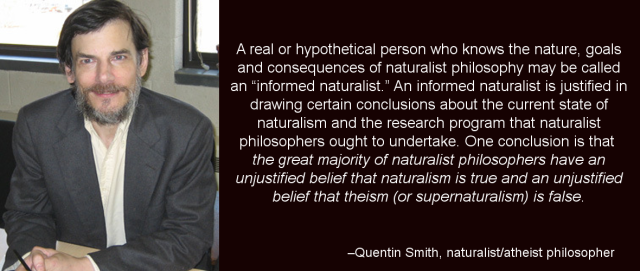

I’ve always been fond of the atheistic philosopher Quentin Smith, since he has made the point constantly that almost all—the “great majority” is his words—of philosophers who reject theism do so without sufficient grounds to do so. They have, to quote Smith, “an unjustified belief that naturalism is true and an unjustified belief that theism is false”:

Today I saw an atheistic argument posted to Twitter in the form of a graphic, which is attributed to Quentin Smith. The post is from Atheist Academy @AtheistAcademy, here

https://twitter.com/AtheistAcademy/status/1160048555370962945

And the actual graphic is

I do not know whether this is an accurate representation of Smith’s argument, or whether he is even the originator of it. I hope not, since it is rather terrible argument—and that is what I’m going to show.

Let’s begin with Premise (1). This is a plausible premise. It is probably worth noting that some physicists, e.g. Stephen Hawking, seem to believe that the laws of nature pre-exist the big bang singularity, to the point where Hawking ascribes them causal powers. But since the premise is plausible, let’s grant it and see what happens.

Premise (2) is also a plausible premise. Again, some philosophers and physicists have disputed it, usually on the the grounds that the putatively “inanimate” must actually be in some sense at least latently animate, since it gives rise to the animate. Leibniz is a good classical example of “panpsychism” and e.g. Colin McGinn of “naturalistic panprotopsychism.” If panpsychism is true in either a strong or weak sense, premise (2) is false, but once again, let’s grant it and see what happens. It is plausible.

Premise (3) is where things start to go wrong. The obvious problem is that premise (3) isn’t a premise at all, but an argument disguised as a premise. The “and consequently” makes it clear that an inference is being made within the premise. Worse, an invalid inference is being made within the premise. Perhaps the inference is hidden inside a single premise in order to hide the invalidity of the inference? I don’t know, but let’s take a closer look.

The premise begins by saying that “no law governs the big bang singularity,” which is dubious even if premise (1) is true. If premise (1) is true, no law preexists the big bag singularity which governs its coming into being, but nothing prevents it coming into being with a determinate—that is, law governed—structure. Nor does premise (2) help, since “being animate” is not necessary for “being law governed.” The premise, in other words, seems to assume that laws of nature neither preexisted the big bang singularity nor came into being along with it—leaving as the only alternative that the laws of nature came into being at some point after the big bang singularity. To claim that nature precedes the laws of nature is at the very least a strange claim, and it seems to me, a prima facie dubious one. It raises such obvious questions as “If nature was not law-governed from the beginning, i.e. the big bang singularity, when and how did it become law-governed?” I think many philosophers and physicists would reject the very idea that something could be “nature” without being “that which is governed by the laws of nature.”

So Premise (3) is off to rocky start, but to make things worse, it draws an invalid inference from the dubious premise which is the first part of the listed premise. Since the big bang is not law-governed, it follows that “there is no guarantee that it will emit a configuration of particles that will evolve into an animate universe.”

Since this argument is meant to demonstrate atheism (or naturalism, which Smith takes to be the same thing), it obviously cannot assume atheism or naturalism as a premise. But what this inference actually says is “if there is no law of nature governing the first state of nature, the big bang singularity, there is no naturalistic guarantee that it “will emit a configuration of particles that will evolve into an animate universe.” Given that the argument is neutral on atheism vs theism, it cannot simply leave out the possibility that God guarantees this by His direct action.

As Plato says, everything happens by choice, chance, or necessity. This argument is making the case that the configuration of particles emitted by the big bag did not happen according to necessity (that is, deterministic law); it then concludes, without warrant, that it must have happened by chance—I see no other possible reading of “not guaranteed.” But this obviously leaves out the third possibility, that it happened according to the will of some agent powerful enough to enact this.

So premise (3) involves a dubious sub-premise and an invalid inference from it. At this point the argument is sunk, but let’s continue.

Premise (4) is valid and trivial, merely restating the second half of premise (3) substituting “the earliest state of the universe” for “the big bang.”

Premise (5) is one of the the worst kinds of premise any atheistic argument can include. It is a “God would have 𝛗ed” premise. Premise (5) and every premise of the form “God would have 𝛗ed” is a non-starter for the simple and sufficient reason that, to be justified in affirming the premise, one would need to omniscient. God could say, with justification, what “God would have done,” but no finite creature, and in particular, no human being, can say so. So whether it is true or not, the premise is unwarranted, and cannot ever be warranted, making the argument unsound—the fact that it collapsed back at premise (3) notwithstanding.

But let’s grant—per impossibile—that we could be justified in a “God would have 𝛗ed” premise. The premise says that if God had created the earliest state of the universe, then God would have guaranteed that it “is animate or evolves into animate states.” What can we say about this? A few things:

(A) We haven’t shown that it isn’t animate—as I noted already, premise (2) just asserts this, without any justification or attempt to refute panpsychism or panprotopsychism.

(B) Granting premise (2) that the earliest state of the universe is inanimate, we haven’t show that God does not guarantee it “evolves into animate states.” All the argument would have shown is that God does not guarantee this by means of the laws of nature. God could, of course, guarantee it by directly setting or causing the proper parameters to occur, instead of building in the parameters that necessitate the occurrence from the beginning. Nothing in the argument has shown that it is a matter of chance.

(C) It is true that it seems less plausible that God would set up a chance mechanism and then monkey with the outcome of the chance mechanism as opposed to setting up a mechanism that is law-governed from the beginning—but since the argument has given us to reason to think that the universe was not law-governed from its creation, only the assertion it was not, we are free to follow our judgment as to what is more plausible. But even on the assumption that the argument is correct, and that the original state of the universe was not law-governed, we have no reason to suppose that God did not directly bring about the outcome He wished. If God did create the universe such that its earliest state were not law-governed but rather had a number of variables and constants that are assigned by no law of nature at all, there is still no reason to thing God did not consciously assign these values, at least no reason given in this argument.

Which brings us to the conclusion (6) that God does not exist. This just doesn’t follow. It doesn’t follow because assumes “God would have 𝛗ed in a certain way.” But even if we were justified in holding “God would have 𝛗ed”, we would still not be justified in “God would have 𝛗ed in a certain way.”

CONCLUSION: This argument rests on premises that range from “plausible” (1) to “fairly dubious” (2) to “almost certainly false” (3). Premise (3) is actually two premises, with an inference hidden inside a premise, and an invalid inference at that. There is simple no reason whatever to accept the first part of (3), and the second part, bundled with it, doesn’t actually follow from the first part, even if it were true, which it almost certainly is not. Premise (5) is prima facie unwarranted since it seems to require omniscience to be warranted, and even if we assume we were warranted in believing it, it doesn’t entail (6), since premise (5) only says that “God would have brought about that Ψ” and then tries to show it is false that “God brought about Ψ” by saying (based on pure assumption from earlier premises) that “God did not bring about Ψ by means Π.” But even if we assume both that “God would have brought about Ψ” and “God did not bring about Ψ by means Π”, these do not entail “God did not bring about Ψ by some other means.”

WORSE STILL, this argument seems to contain a latent argument for THEISM. Let us assume that it is true that, as the argument asserts, the initial state of universe was such it was not determined by any law of nature that the universe be such as would be capable of sustaining and would produce and sustain animate beings. To return to Plato’s trilemma, we would have to say “Since the earliest state of the universe did in fact generate a universe that is capable of sustaining animate being, actually produced animate being, and sustains animate being, this happened either by chance or by conscious, intelligent choice. The probability of this happening by chance is so low as to be mathematically indistinguishable from 0. Therefore, almost certainly, the production of the universe was a result of conscious, intelligent choice.”

In short, this failed argument for atheism actually yields a very strong form of the fine tuning argument for God, with only minimal adjustment—namely, the addition of the evident fact that animate being, conscious life, does in fact exist in our universe. By ruling out necessity as a cause of this, the argument leaves us to decide whether chance or conscious choice is responsible for the universe, and the thing is unfathomably improbable to have happened by chance, than otherwise sensible people frequently posit the existence of an undetectable, unfalsifiable “multiverse” just so they can get “necessity” back on the table as a cause! But that is just what is ruled out here.

This argument leaves us with the stark choice of “our life sustaining universe was either the result of an infinitesimal chance, more than winning a trillion trillion lotteries in a row, or to the conscious intelligent creation by a being powerful enough to do so.” At this point, it is almost trivial to say that a conscious, intelligent agent is by far the best explanation.