This is Chapter 2 of Pavel Florensky’s Pillar and Ground of the Truth, “DOUBT.”

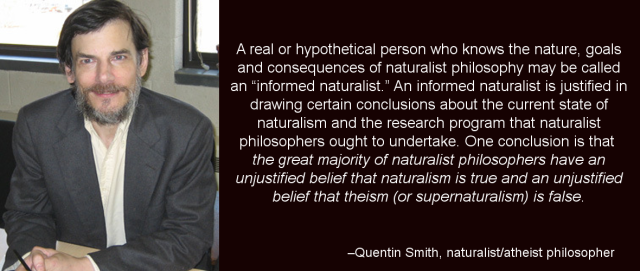

PAVEL FLORENSKY is sometimes called “the da Vinci of Russia.”

Although this book is expensive in English, it is one of the more important works of the 20th century. I highly recommend it to everyone: PILLAR AND GROUND OF THE TRUTH.

This Chapter is long and difficult (as was typing it in by hand—you’re welcome) but well worth serious reading, study, and reflection. I did give some serious thought to leaving out Florensky’s etymological-phenomenological examinations of the nature of truth is Russian, Greek, Latin, and Hebrew, respectively, since I think the dialectic of realism, rationalism, and skepticism is the main point, but I have decide to leave it intact, especially in the light of a recent Twitter exchange that drove home to me just how inadequate the typical phenomenology of truth is. Having long been acquainted with Heidegger, I’m aware of how deep these waters can get, and for some, it will be the first time they have thought seriously about truth is this way. Heidegger also taught me that the things we think about the least are the most important and often the simplest in some respects: Being, Truth, the Good, Beauty. We constantly take our immediate familiarity with these things, since every human act and experience involves them, as adequate knowledge of these things, which it is not. Heidegger’s question, which was also Plato’s (via the Eleatic Stranger) “What do we really mean by Being?” remains inadequately answered—indeed, Heidegger did not succeed in clarifying the question fully, although he accomplished a good deal. Similarly, Pilate’s question, “What is truth?” asked in a spirit of utter indifference, the antipodes of Socrates (Nietzsche calls in the only noble expression in the New Testament)—this too, the question of Truth, has not been answered adequately, even today. No, today we are so far from answering the question of Truth, that the Postmodernists deconstruct it and the Analysts deflate it. “A plague o’ both your houses!”

This text on Truth and Certainty and Doubt is as worthwhile as it is difficult.

I’m writing this primarily so it exists somewhere on the internet and people who otherwise would not be able to read it, can and do read it. Florensky should be far more famous than he is, given his ability as a thinker, but that deserved fame was one more thing swept away when the Communists murdered him and unpersoned him and sought to remove him from history. Some Orthodox Christians regard Florensky as a martyr and even a saint. Others hold his theology to be heretical. I can’t speak to these matters, but will vouch for his depth as a thinker, in Heidegger’s sense of the term.

Those of you familiar with Heidegger will be astonished to learn that this was written over a decade prior to Being and Time.

Enjoy and God bless,

_Eve

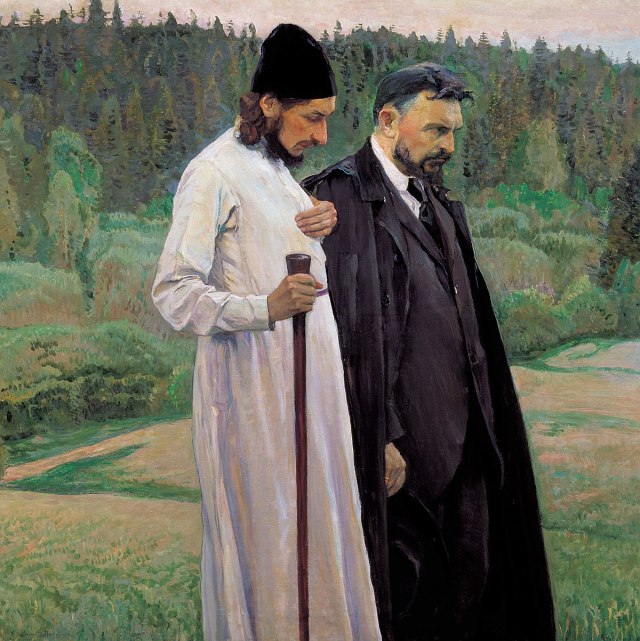

Pavel Florensky and Sergei Bulgakov

___________________________________________________________________________________

His ornari aut mori. “To receive either a crown or death.”

III. Letter Two: DOUBT

“The Pillar and Ground of the Truth.” But how can one recognize it?

This question inevitably leads us into the domain of abstract knowledge. For theoretical thought “the Pillar of the Truth” is certainty.

Certainty assures me that the Truth, if I have attained it, is in fact what I sought. But what did I seek? What did I mean by the word “Truth”? In any case, I meant something so total that it contains everything and therefore something that its name expresses only by convention, partially, symbolically. The Truth, according to the philosopher, is the “all-one existent.” But then the word “truth,” does not cover its own proper content and in order to disclose the meaning of the word truth if only approximately, in view of a preliminary understanding of our search, we must see what aspects of this concept have been taken into consideration by different languages, what aspects of this concept have been underscored and fixed through its etymological shells among different peoples.

Our Russian word for truth, “istina,” is linguistically close to the verb “est” [to be]. Hence, “istina,” according to the Russian understanding of it, embodies the concept of absolute reality: istina is “what is,” the genuinely existent, to ontōs on or ho ontōs on, in contradistinction to what is imaginary, unreal, unactual. In the word “istina,” the Russian language marks the ontological aspect of the idea. Therefore, “istina” signifies absolute self-identity and, hence, self-equality, exactness, genuineness. Istyi, istinnyi, istovyi [true, authentic, real] are words that issue from the same etymological nest.

Scholastic philosophy too did not shy away from an ontological understanding of the truth. For example, one can point to the semi-Thomist Dominican John Gratideus from Ascoli († 1341), who decisively insisted that “Truth” must be understood not as equality or agreement, which is introduced into things by a cognitive act of reason, but as the equality that the thing injects into its existence from outside: “Formally, truth is the equality or conformity that the thing itself , insofar as it is thought, injects into itself in the nature of things outside.”

Let us now turn to the etymology. Is-ti-na and its derivatives (cf. the Lettish ist-s, its-ens-s) are related to es-t’, est-e-stvo (to be, essence). They can be compared with the Polish istot-a [entity], istot-nie (really), istniec (to exist really). Others have the same view of the etymology of the word “istina.” According to the definition of V. Dal’, for example, “istina is all that is genuine, authentic, exact, just, that which is. All that is [est’] is istina. Are not est’ and estina, istina one and the same?” Dal’ asks. Mikloshich, Mikutsky, and our specialist in old words, F. Shimkevich, are of the same opinion. It is clear from this that, among the various meanings of the word “istyi,” we find “closely resembling.” Accord to the old explanation of a certain merchant, A. Fomin, “istyi” means similar, exact. Thus, he explains the ancient locution “istyi vo otsa” to mean “exactly like the father.”

This ontologism in the Russian understanding of truth is strengthened and deepened for us if we consider the etymology of the verb est’. Est’ come from the root es, which in Sanskrit gives as (e.g., ásmi = esmi; asti = esti). Esm’, est’ can without difficulty be related to the Old Slavic esmi; the Greek eimi (esmi); the Latin (e)sum, est; the German ist; the Sanskrit asmi, asti, etc. But in accordance with certain hints in Sanskrit, this root es signified—in its most ancient, concrete phase of development—to breath, hauchen, athmen. In confirmation of this view of the root as, Curtius points to the Sanskrit words as-u-s (the breath of life), asu-ras (vital, lebendig); and, equivalent to the Latin os, mouth, the words âs, âs-ja-m, which also signify mouth; the German athmen is also related to this. Thus, “est’” originally meant to breathe. Respiration, or breath, was always considered to be the main attribute and even the very essence of life. And even today, the usual answer to “Is he alive?” is “He’s breathing.” Whence the second, more abstract meaning of “est’“: he’s alive, he has strength. Finally, “est’” acquires its most abstract meaning, that of the verb that expresses existence. To breath, to live, to be—these are the three layers in the root of es in the order of their descending concreteness, an order than, in the opinion of linguists, corresponds to their chronological order.

The root as signifies an existence as regular as breathing (ein gleichmässig fortgesetze Existenz) in contrast to the root bhu, which one finds in byt’, fui, bin, phuō, etc., signifying becoming (ein Werden).

Pointing to the link between the notions of breathing and existence, Renan gives a parallel from the Semitic languages, namely the Hebrew verbal substantive haja (to happen, to appear, to be) or hawa (to breath, to live, to be). In these words he seems an onomatopoeia of the process of breathing.

Thanks to this opposition between the roots of es and bhu, they complement each other: the former is used exclusively in forms of duration, derived from the present. The latter is primarily use in those forms of time which, like the aorist and the perfect, signifying an accomplished becoming.

Returning now to its Russian understanding, we can say that the truth [istina] is existence that abides, that which lives, living being, that which breathes, i.e., that which possesses the essential condition of life and existence. Truth as the living being par excellence—that is the conception the Russian people have of it. To be sure, it is not difficult to see that it is precisely this conception of truth that forms the distinctive and original feature of Russian philosophy.

The ancient Greek underscores a wholly other aspect of truth. Truth, he says, is alētheia. But what is this alētheia? The word alēthe(s)ia or, in the Ionian form, alētheie, like the derivatives alēthes (truthful), alētheno (I conform to truth), and so forth, consists of the negative particle a (alpha privativum) and *lēthos, lathos in Doric. The latter word, from the root ladho, has the same root as the verb lathe, the Ionic lēthō, and lanthanō (I pass by, I slip away, I remain unnoticed, I remain unknown). In the medium voice this verb acquires a sense of memoria labor, I let slip from memory, I lose for memory (i.e. for consciousness in general), I forget. Connected are with this later nuance of the root lath: lēthē, the Doric latha, lathosuna, lēsmosuna, lēstis, i.e., forgetting and forgetfulness, lēthargos, a summons to sleep, Schlafsucht, as the desire to immerse oneself in a stage of forgetting and unconsciousness, and, further, the name of a pathological sleep, lethargy. The ancient of death as a transition to an illusory existence, almost to self-forgetting and unconsciousness, and, in any case, to the forgetting of everything earthly, finds its symbol in the image of the shades’ drinking of water from the underground river of Forgetfulness, “Lethe.” The plastic image of the “water of Lethe,” to Lēthēs hudōr and a whole series of expressions, such as meta lēthēs, i.e. in forgetfulness; lēthēn echein, i.e., to have forgetting, that is, to be forgetful; en lēthēs tinos eina, i.e. to forget something; lēsmonsunan thestai, to bring to a state of forgetting; lēstin iskein ti, i.e. to forget something, and so forth—all this taken together testifies that forgetting for the Greek understanding was not merely a state of absence of memory, but a special act of the annihilation of a part of the consciousness, an extinguishing in the consciousness of a part of the reality of that which is forgotten, in other words, not a lack of memory but a power of forgetting. The power of forgetting is the power of all-devouring time.

All is in flux. Time is the form of existence of all that is, and to say “exists” is to say “in time,” for time is the form of the flux of phenomena. “All is in flux and moving, and nothing abides,” complained Heraclitus. Everything slips away from consciousness, flows through the consciousness, is forgotten. Time, chronos, produces phenomena, but, like its mythological image, Chronos, it devours its children. The very essence of consciousness, of life, of any reality is in their flux, i.e., in a certain metaphysical forgetting. The most original philosophy of our day, Henri Bergson’s philosophy of time, is wholly built on this unquestionable truth, on the idea of the reality of time and its power. But despite all the unquestionableness of the latter, we cannot extinguish the demand for that which is not forgotten, and that which is not forgettable, for that which “abides” in the flux of time. It is this unforgettable which is a-lētheia. Truth, in the understanding of the Greeks, is a-lētheia, something capable of abiding in the flux of forgetfulness, in the Lethean currents of the sensuous world. It is something that overcomes time, something that does not flow but is fixed, something eternally remembered. Truth is the eternal memory of some Consciousness. Truth is value worthy of and capable of eternal remembrance.

Memory desires to stop movement; memory desires to freeze the motion of fleeting phenomena; memory desires to place a dam in front of the flux of becoming. Thus, the unforgettable existence that is sought by consciousness, this alētheia, is a fixed flux, an abiding flow, an immobile vortex of being. The very striving to remember, this “will to unforgettableness,” surpasses the rational mind. But the latter desires this self-contradiction. If, in its essence, the concept of memory transcends the rational mind, then Memory taken in its highest measure, i.e., the Truth, a fortiriori transcends the rational mind. Memory-Mnemosyne is the mother of the muses, the spiritual activities of mankind, the companions of Apollo, of Spiritual Creativity. Nevertheless, the ancient Greeks demand of Truth the same quality that is indicated by Scripture, for there it is said that “the truth of the Lord endureth forever” (Ps. 117:2) and that “Thy truth is unto all generations” (Ps. 119:90).

As is well known, the Latin word for truth, veritas, derives from the root var. In view of this, the word veritas is considered to have the same root as the Russian words vera (faith) and verit’ (to believe), and the German words wahren, to preserve and protect, and wehren, to prevent, as well as to be strong. Wahr, Wahrheit, truthful, truth, are also related words, like the French verité, which directly derives from the Latin veritas. That the root var originally refers to the cultic domain is seen, as Curtius tells us, from the Sanskrit vra-ta-m, sacred rite, vow; from the Zend zarena, faith; and from the Greek bretas, something revered, a wooded or stone idol; the word heortē (instead of e-For-tē), cultic worship, religious feast, also appears be related. The cultic connection of the root var and especially the word veritas is clearly seen in a survey of Latin words of the same root. Thus, there is no doubt that the verb ver-e-or or re-vereor, which is used in classical Latin in the more general sense of I am apprehensive of, I take care, I am afraid, I am terrified, I revere, I respect, I tremble with fear, originally referred to the mystical dread and to the caution that was provoked by this dread when one came too close to holy beings, places, and objects. Taboo, the sacred, the holy, is what forces a man vereri. This led to the Catholic title of spiritual persons: reverendus. Reverendus or reverendissimus pater is a person towards whom one must behave respectfully, cautiously, fearfully. Otherwise, something bad could happen. Verenda-orumor or partes verendae are pudenda, and it is well known that antiquity had a reverent attitude toward them, treated with fearful religious respect. Then, the noun verecundia, religious fear, modesty, the verb verecundor, I have fear, and the adjective verecundus, fearful, shameful, decent, modest, once again point to the cultic domain of the application of the root var. It is clear from this that, strictly speaking, verus means protected or grounded in the sense of that which is the object of taboo or consecration. Verdictum, the verdict of a judge has, of course, the sense of the religiously obligatory judgment of persons who head a cult, for the law antiquity is only an aspect of cult. The meaning of other words, such as veridicus, veriloquium, etc., are clear without explanation.

A. Suvorov, the author of the Latin etymological dictionary, indicates that the Russian verb govoriu, reku [I speak, I say] express the original sense of the root var. But, on the basis of what has been said above, it is unquestionable that, if the root var really means “to speak,” it is precisely attributed to this word to this word by all antiquity, that is, in the sense of a powerful, vatic word (be it ritual consecration or prayer) which is capable of making its object not only juridically and nominally but also mystically and really a source of fear and trembling. Thus, strictly speaking, vereor means “the power of ritual consecration exerted over me.”

After these preliminary considerations it is not difficult to guess the meaning of the word veritas. Let us first remark that this word, which is of late origin, had wholly belonged to the domain of law and acquired only with Cicero a philosophical and generally theoretical sense, a sense that refers to the domain of knowledge. Even in the generally moral sense of sincerity, parrēsia, this word is encountered before Cicero just once, in Terence, in the phrase: “obsequium amicos, veritas odium parit” (obsequiousness produces friends, while sincerity produces hatred). Furthermore, although in Cicero the word veritas at once acquires a wide application, this is primarily the legal and, in part, the moral domain. Here, veritas means either a real situation of a juridical case as opposed to its false clarification by one of the parties involved, or justice, or finally the just cause of the plaintiff. It is only rarely equated with “truth” as we tend to understand it.

The juridical nuance of veritas, a word religiously juridical in its root and morally juridical in its origin, was subsequently preserved and even grew more pronounced. In later Latin the word even came to have a purely juridical meaning. According to du Cange, veritas means depositio testis, the disposition of a witness, veridictum. Veritas then came to mean inquisitio judicaria, judicial inquest. It also came to mean right, privilege, particularly with respect to property, and so forth.

The ancient Hebrews, and the Semites in general, captured in their language a special aspect of the idea of Truth: the historical aspect, or more precisely, the theocratic aspect. Truth for them was always the Word of God. For the Hebrew, the irrevocability, certainty, and reliability of this Divine promise is what characterized the Truth. Truth is Reliability. “It is easier for heaven and earth to pass away than for one tittle of the law to fail” (Luke 16:17). The Truth as it is represented in the Bible is precisely this absolutely irrevocable and unalterable “law.”

The Hebrew word ’emet or, in colloquial pronunciation, emes, truth, has as its basis the root ‘mn. The verb ‘man derived therefrom means, strictly speaking, I supported, I propped up. This main meaning of the verb ‘aman is strongly indicated by nouns of the same root from the domain of architecture: ‘omenah, column, and ‘amon, builder, master, and, in part, by ‘omen, pedagogue, i.e. builder of children’s souls. The intransitive middle sense of the verb ‘aman, was supported, was propped up, then serves as the point of departure for a whole brood of words that are fairly removed from the main meaning of the verb ‘aman, i.e. was strong, firm (as supported, as propped up), and therefore was unshakeable. From this we get the meanings: suitable for use as a support to lean upon without damage to it, and finally, was faithful. From this we get Amen, meaning: my word is firm, verily, of course, thus it must be, fiat. It serves as a formula to seal a union or a vow. It also used to conclude a doxology or a prayer (here it is said twice). The meaning of the word “amen” is well clarified from Rev 3:14: “These things saith the Amen, the faithful and true witness.” Cf. Is. 65:16: “‘elohe-‘amen, the God that one should trust.” From here one can understand the whole combination of meanings of ’emet (instead of amenet). Its most immediate meanings are firmness, stability, durability, and therefore safety. Further, we get faith-faithfulness, fides, by virtue of which he who is constant in himself preserves and fulfills the promise, the concepts of Treue and Glaube. One can then also understand the connection of this latter concept with the honesty and wholeness of the soul. As the distinguishing characteristic of a judge or a judicial sentence, ’emet therefore signifies justice, truthfulness. As the distinguishing characteristic of the inner life, it is opposed to pretense and has the meaning of sincerity, primarily sincerity in the worship of God. Finally, ‘meet corresponds to the Russian word istina (truth) in opposition to falsehood. This is precisely how the word is used in Gen. 42:16, Deut 22:20, 2 Sam. 7:28. Also see 1 Kings 10:6, 22:16, Ps. 15:2, 51:6, etc.

Derived from this latter nuance the word ’emet is the term meames, which is used by Hebrew philosophers, e.g. Maimonides, “to describe people who, not being satisfied with authority and custom, strive for intellectual knowledge of truth.”

Thus, for the Hebrews, Truth really is the “reliable word,” “reliability,” “the reliable promise.” And since to “put … your trust in princes … in the son of man” (Ps. 146:3) is vain, the sole reliable word is the Word of God; Truth is God’s unalterable promise, which is insured by the Lord’s reliability and immutability. Thus, for the Hebrews, Truth is not an ontological concept, as it is for the Slavs. It is not an epistemological concept, as it is for the Greeks. And it is not a juridical concept, as it is for the Romans. Instead, it is a historical, or rather, a sacred-historical concept, a theocratic concept.

The four nuances of the concept of truth observed by us can be combined in pair fashion, in the following manner: the Russian Istina and the Hebrew ’emet refer primarily to the Divine content of the Truth, while the Greek Alētheia and the Latin Veritas refer to its human form. On the other hand, Russian and Greek terms have a philosophical character, while the Latin and Hebrew terms have a sociological character. By this I mean that, in the Russian and Greek understanding, Truth has an immediate relation to every person, while, for the Romans and the Hebrews, it is mediate by society. All that we have said about the division of the concept of the truth can be conveniently summarized in the following table:

______________________________________________________________________________________

………………………………………… According to Content According to Form

Immediate Personal Relation Russian Istina Greek Alētheia

Socially Mediated Relation Hebrew ’emet Latin Veritas

______________________________________________________________________________________

“What is truth?” Pilate asked of the Truth (see John 18:38). He did not receive an answer. He did not receive an answer because the question was vain. The Living Answer stood before him, but Pilate did not see the Truth’s truthfulness. Let us suppose that the Lord answered the Roman Procurator not only with this screaming silence but also with the quiet words, “I am the Truth.” But even then the questioner would have remained without an answer, for he would not have known how to recognize the Truth as truth, could not have been convinced of its genuineness. The knowledge Pilate lacked, the knowledge that all of mankind lacks above all, is knowledge of the conditions of certainty.

What is certainty? It is the discovery of the proper character of truth, the recognition in truth of a particular feature that distinguishes it from untruth. Psychologically, this recognition is expressed as untroubled bliss, the satisfied thirst for truth.

“Ye shall know the Truth (tēn alētheian), and the Truth (hē alētheia) shall make you free.” (John 8:32). From from what? Free in general from sin (see John 8:34), from every sin, free (in the domain of knowledge) from everything that is untruthful, from everything that does not conform with the truth. “Certainty,” says Archimandrite Serapion Mashkin, “is the feeling of truth. Certainty appears when we pronounce a necessary judgment and consists in the exclusion of the suspicion that the judgment pronounced will change some time or somewhere. Certainty is therefore the intellectual feeling of accepting the judgment pronounced as a true one.” “By a criterion of truth, ” the same philosophers says in another work, “we mean the state of the truth-possessing spirit, a state of complete satisfaction, of joy, in which there is no doubt whatever that the stated proposition conforms to genuine reality. This state is reached when a judgment about something satisfies a proposition called a measure of truth or its criterion.”

The problem of the certainty of truth is reducible to the problem of finding a criterion. The entire demonstrative force of a system is focused, as it were, in the answer to this problem of finding a criterion.

Truth becomes my possession through an act of my judgment. By my judgment, I receive truth into myself. Truth as truth is revealed to me by my affirmation of it.

Consequently, the following question arises: If I affirm something, by what do I guarantee for myself its truthfulness? I receive something into myself as truth. But should I do this? Is not the very act of my judgment what removes me from the truth I seek? In other words, what sign should I see in my judgment so as to be inwardly at peace?

Every judgment is either through itself or through something else, i.e. it is given directly or reached indirectly as a consequence of something else. The indirect judgment has in this something else its sufficient ground. If it is not given through itself or mediated by something else, it lacks all real content and rational form, i.e. it is not a judgment at all but only sounds, flatus vocis, vibrations of the air, nothing more. Thus, every judgment necessarily belongs to at least one of two classes, direct or indirect. Let us now examine each of these classes separately.

[[[ Eve note: It will become immediately apparent that what Florensky is approaching in “direct knowing” and “indirect knowing” are νόησις [Greek: direct intellectual knowing comparable to ‘seeing’ with the mind; sometimes called Intuition in English] and λόγος [Greek: the human power of discursive reasoning, that is step by step movement in chains of reasoning; the Discursivity; syn. διάνοια; διαλέγεσθαι]. νόησις and λόγος. Intuition and Discursivity. Seeing and Saying. The Socratic-Platonic-Aristelian tradition, i.e. the Western tradition, maintains that all human thought is a mixture of these two activities, which compliment one another, although νόησις is regarded as decisively higher than λόγος. ]]]

[Direct Knowledge as Intuition of the Given, or]

REALISM

A judgment given directly is the self-evidence of Intuition, evidentia, enargeia. It subsequently becomes fragmented.

The self-evidence can be the self-evidence of sense experience, and then the criterion of truth is the criterion of empiricists of external experience (the empirio-criticists, etc.) “All things that can be reduced to direct perceptions by the sense organs are certain. The perception of an object is certain.

The self-evidence can be the self-evidence of intellectual experience, and the criterion of truth in this case is the criterion of the empiricist of internal experience (that transcendentalists, etc.). “All things that can be reduce to axioms of reason are certain. The self-perception of a subject is certain.”

Finally, the self-evidence of intuition can be the the self-evidence of mystical intuition. A criterion of truth as it is understood by the majority of mystics (especially Indian mystics) is obtained: “All things that remain when everything that is irreducible to the perception of the subject-object is filtered out are certain. Only the perception of the subject-object in which there is no split into subject and object is certain.”

These are the three kinds of self-evident intuition. But all three of these aspect of what is given (sensuous-empirical, transcendental-rationalistic, and subconscious-mystical) have one insufficiency in common: their naked, unjustified givenness. This givenness is perceived by consciousness as something external to itself, as something compulsory, mechanical, self-imposing, blind, and dull, as, in the final analysis, something irrational and therefore conditional. The mind does not see the internal necessity of the perception. It sees only an external necessity, i.e., a necessity forced upon it, an inevitability. To the question, “Where is the ground of our judgment of perception?” all these criteria answer: “This ground lies in the fact that sensuous perception, intellectual apprehension, or mystical awareness is precisely the very same perception, apprehension, or awareness.” But why is “this” precisely “this,” and not something else? What does the reason of this self-identity of the immediately given consist in? “In consists in the fact,” it is said, “that, in general, every given is itself: every A is A.”

A = A. That is the final answer. But this tautological formula, this lifeless, thought-less, and therefore meaningless equality A = A, is, in fact, only a generalization of the self-identity that is inherent in every given. But by no means is this formula an answer to our question “Why?” In other words, this equality transfers our particular question from a single given to givenness in general. In displays our painful state of the moment on a gigantic scale, as if projecting it by a magic lantern upon the whole of being. If previously we had bumped against a stone, it is now announced to us that this is not an isolated stone but a solid wall, a wall that encompasses the entire domain of our enquiring mind.

A = A. That says everything. It says: “Knowledge is limited by conditional judgments.” Or simply: “Be silent, I tell you!” Mechanically stopping up our mouths, this formula dooms us to abide in the finite and therefore in the accidental. This formula affirms in advance the separateness and egotistical isolation of the ultimate elements of being, this rupturing all rational connection between them. To the question “Why?” or “On what ground?” it repeats “sic et non alter, thus and not otherwise,” interrupting the questioner but not being able to satisfy him and to teach self-limitation. Every philosophical construction of this type follows the paradigm of the following conversation I once had with an old female servant:

I: “What is the sun?”

She: “It is our little sun.”

I: “No, I mean what is it?”

She: “It’s the sun.”

I: “By why does it shine?”

She: “The sun is the sun, that’s why it shines. It shines and shines. Look, see what the sun is like.”

I: “But why?”

She: “Good God, Pavel Aleksandrovich, as if I know! You’re the educated and learned one. We’re ignoramuses.”

It is self-evident that the criterion of givenness that is applied by the overwhelming majority of philosophical schools in one way or another cannot give certainty. From “is,” no matter how deep it lies in nature or in my being, or in the common root of the one and the other, it is impossible to extract “necessary.”

Furthermore, even if we did not notice this blind character of the naked tautology A = A, even if we did not suffocate in this “it is because it is,” reality would force us to direct our mental gaze upon it.

That which is accepted as the criterion of truth in virtue of its givenness turns out to be violated by reality on all sides.

By a strange irony, precisely that criterion which seeks to base itself exclusively on its own factual lordship over everything, on the right of power over every actual intuition, is in fact violated by every factual intuition. The law of identity, which pretends to absolute universality, turns out to have a place nowhere at all. This law sees its right in its actual givenness, but every given actually rejects this law toto genere, violating it in both the order of space and the order of time—everywhere and always. In excluding all other elements, every A is excluded by all of them, for if each of these elements is for A only not-A, then A over against not-A is only not-not-A. From the viewpoint of the law of identity, all being, in desiring to affirm itself, actually only destroys itself, becoming a combination of elements each of which is a center of negations, and only negations. Thus, all being is a total negation, one great “Not.” The law of identity is the spirit of death, emptiness, and nothingness.

Once present givenness becomes the criterion, it is such absolutely everywhere and always. Therefore, all mutually exclusive A’s as givens are true; everything is true. But this annuls the power of the law of identity, for this law then turns out to contain an internal contradiction.

But there is really no need to point out that one person perceives in one way while another person perceives in another way. One does not inevitably have to refer to the self-disharmony of consciousness in space. Such multiplicity is also manifested by every individual subject. Change occurring in the external world, in the inner world, and finally in the world of mystical perceptions proclaims harmoniously: “The previous A is not equal to the present A, and the future A will differ from the present A.” The present opposes itself to its past and its future in time just as, in space, a thing is opposed to all things that lie outside it. In time as well, consciousness is self-disharmonious. Contradiction is everywhere and always, but identity is nowhere and never.

The law A = A becomes a completely empty schema of self-affirmation, a schema that does not synthesize any real elements, anything that is worth connecting with the “=” sign. “I = I” turns out to be nothing more than a cry of naked egotism: “I!” For where there is no difference, there can be no connection. There is therefore only the blind force of stagnation and self-imprisonment, only egotism. Outside of itself, I hates every I, since for it this I is not-I; and hating, I strives to exclude this I from the sphere of being. And since the past I (I in its past) is also considered objectively, i.e., since it also appears as not-I, then it too is irreconcilably subject to exclusion. I cannot bear itself in time and negates itself in all ways in the past and future. Thus, since the naked “now” is a pure zero of content, I hates the whole of its concrete content, i.e., the whole if its life. I turns out to be a dead desert of “here” and “now.” But what then is governed by the formula “A = A”? Only a fiction (an atom, a monad, etc.), only a hypostatized abstraction of a moment and a point, which, in themselves, do not exist. Yes, the law of identity is an unlimited monarch. But its subjects do not object to its autocracy only because they are bloodless phantoms, without reality, because they are not persons but only rational shades of persons, i.e., things that do not exist. This is Sheol. This is the kingdom of death.

Let us recapitulate what we have said. Only that is rational, i.e., only that conforms to the measure of rationality and satisfies the demands of rationality, which is isolated from everything else, which is not mixed with anything else, which is self-contained, in short, which is self-identical. Only A that is equal to itself and unequal to what is not A is considered by rationality as genuinely existent, as to on, to ontōs on, as “truth.” On the other hand, to everything that is unequal to itself or equal not to itself, rationality refuses to attribute genuine being, ignores it as “non-existent” or as not truly existent, as to mē on. Rationality only tolerates this mē on, only admits it as not-truth, by capturing it, it use Plato’s expression, through “some sort of illegitimate argument,” hapton logismōi tini nothōi (nothos, strictly speaking, means “bastard; of illegitimate birth.”

Only the first, i.e., the “existent”, is recognized by rationality, which rejects the second, i.e. the “not-existent.” Rationality pins on this “non-existent” the label to mē on, does not notice it, making believe that it does not exist at all. For rationality only an affirmation about the “existent” is truth. By contrasts, a declaration about the “non-existent” is, strictly speaking, not even a declaration. It is only a doxa, an “opinion,” only the appearance of a declaration, devoid of the power of a declaration. It is only a “manner of speaking.”

But for this reason it turns out that the rational is at the same time unexplainable. To explain A is to reduce it to “something else,” to not-A, to that which is not A and which therefore is not-A. It is the derive A from not-A, to generate A. And if A really satisfies the demand of rationality, if it is really rational, i.e., absolutely self-identical, it is then unexplainable, irreducible “to something else” (to not-A), underivable “from something else.” Therefore, rational A is absolutely non-reasonable, blind A, untransparent to reason. That which is rational is non-reasonable, non-conformable to the nature of reason. Reason is opposed to rationality, just as rationality is opposed to reason, for they have opposite demands. Life, flowing and non-self-identical, might be reasonable; it might be transparent to reason (we have not yet found out if this is the case). But, precisely for this reason, life would be non conformable with rationality, opposed to rationality. It would rip apart the limitedness of rationality. And rationality, hostile to life, would in turn rather seek to kill life than agree to receive life into itself.

Thus, if the criterion of self-evidence is insufficient theoretically, as something that stops the seeking of the spirit, it is also of no use practically, since it cannot achieve its claims even within the limits it has set for itself. The immediate givenness of all three kinds of intuition (objective, subjective, subjective-objective) do not give certainty. This is a radical condemnation of all philosophical dogmatic systems. And we do not exclude Kant’s system, for which sensuousness and reason with all its functions are simple givens.

[[[ EVE NOTE: Having brought out the aporia in Intuition, namely the blindness of such intuition to any Why? of simply seeing the simple given, Florensky turns from the REALISM of INTUITION, to the RATIONALISM of DISCURSIVE RATIONALITY, the kind of reasoning that proceeds in steps and makes chains of inference in order to give proofs and demonstrations. ]]]

RATIONALISM

I now turn not to immediate but mediated judgement, to what is commonly called discursion, discursivity, for here reason discurrit, runs to some other judgment.

By its very name, the certainty of this judgment consists in its reducibility to another judgment. The question about the ground of a judgment is answered not by this judgment itself but by another judgment. In the other judgment, the given appears as justified; it appears in its truth. Such is the relative proof of one judgment on the basis of another. To prove relatively means to demonstrate how one judgment forms the consequent of another, how it is generated by another. Reason shifts focus here to a grounding judgment. But this judgment cannot be simply given, for then the whole matter would be reduced to the criterion of self-evidence / intuition. This judgment too must be justified in another judgment. And the next judgment leads to another judgment. And it goes on and on. But this is very similar to how our forebears spoke. They constructed entire chains of explanatory links. For example, we read in a Serbo-Bulgarian manuscript of the 15th century:

“Tell me: What supports the earth? The high water. But what supports the water? A great, flat rock. But what supports the rock? Four golden whales. But what supports the golden whales? A fiery river. But what supports the fire? Another fire that is twice as hot. But what supports the other fire? An iron oak that is rooted in the power of God.”

But where is the end? Our forebears ended their “explanations,” or “justifications,” of the present reality by referring to the attributes of God. But since they do not show why these attributes should be accepted as justified, our forebears’ reference to God’s will or power (if it was not a direct rejection of explanation) must have had a formal significance, the significance of an abbreviated representation of the continuation of the explanatory process. Modern language uses the abbreviation “etc.” for this purpose. But the meaning of both answers is the same: They are used to attempt to show that there is no end to this justification of the given reality. In fact, when someone, abandoning his childish faith, has entered upon the path of explanations and justifications, he inevitably encounters Kant’s rule that “the wildest hypotheses are more tolerable than recourse to the supernatural.” Therefore, to the question “Where is the end?” we answer, “There is no end.” Instead, there is an infinite regression, regressus in indefinitum, a descent into the gray fog of the “bad” infinite, a never-ending fall into infinitude and bottomlessness.

This should not surprise us. It could not be otherwise. For if the series of descending justifications were broken somewhere, the broken link would be a dead end, and this dead end would destroy the very idea of certainty of the type being considered now, i.e. of abstract-logical, discursive certainty, in contradistinction to the type considered previously, i.e. concretely intuitive certainty. The possibility of justifying every step of the descending ladder of judgments, i.e., the incontrovertible, constant possibility of being able to descend at least one step below any given step, i.e., the constant admissibility of the transition from n to (n + 1), whatever n is, this possibility contains the whole essence, the whole reasonableness, the whole meaning of our criterion in the same way that an egg contains the embryo.

But this essence of the criterion is also its Achilles’ heel. Regressus in indefinitium is given in potentia, as a possibility but not in actu, not as a finished reality, a reality that is realized at a given time and in a give place. A reasonable demonstration only gives rise in time to the dream of eternity but never makes it possible to touch eternity itself. Therefore, the reasonableness of a criterion, the certainty of truth, is never given as such in reality, actually, in its justifiability.

In its immediately given concreteness, intuition is something actual, although it is blind (to its ground) and therefore conditional. Intuitions could not satisfy us. But discursion, in its always only mediately justified abstractness, is invariably only something possible, unreal, although (and this makes up for it!) it is reasonable and unconditional. Of course, it, too, we consider unsatisfactory.

Let me say in simply: Blind intuition is a bird in the hand while rational discursion is a bird in the bush. If the former provides the nonphilosophical satisfaction by its presence and its reliability, the latter is, in fact, not attained reasonableness but only a regulating principle, a law for the activity of reason, a road on which we must walk eternally in order … in order never to reach any goal. A rational criterion is a direction, not a goal.

If blind and absurd intuition can still give comfort to the nonphilosophical mind in its practical life, discursion is, of course, suitable only for the literary exercises of school or for the self-satisfaction of the scholar, for those whose “profession” is philosophy but who have never partaken of it.

An impenetrable wall and an uncrossable sea; the deadliness of stagnation and the futility of unceasing motion; the obtuseness of the golden calf or the eternal incompletion of the Tower of Babel; i.e. a stone idol and “ye shall be as gods” (Gen. 3:5); present reality and never-finished possibility; formless content and contentless form; finite intuition and endless discursion; realism and rationalism—those are the Scylla and Charybdis on the way to certainty. A very sad dilemma! The first way out is to embrace obstinately the self-evidence of intuition, which in the last analysis is reduced to the givenness of a certain organization of reason, whence comes Spencer’s notorious criterion of certainty. The second way out is to plunge hopelessly into rational discursion, which is empty possibility, to descend lower and lower into the depths of motivation.

But neither way out provides satisfaction in the search for Incorruptible Truth. Neither way out leads to certainty. Neither way out provides a sight of the “Pillar of the Truth.”

Can one not ascend above both obstacles?

We return to the intuition of the law of identity.

SKEPTICISM

But, having exhausted the resources of realism and rationalism, we involuntarily turn to skepticism, i.e., to an examination, a critique, of the self-evident judgment.

As establishing the de facto inseparability of the subject and its predicate in consciousness, this judgment is assertoric. A link between the subject and the predicate exists, but it does not have to exist. There is as yet nothing in the character of this link that makes it apodictically necessary and irrevocable. The only thing that can establish such a link is proof. To prove is to show why we consider the predicate of a judgment apodictically linked with the subject. Not to accept anything without proof is not to admit any judgments except apodeictic ones. The basic requirement of skepticism is to consider every unproved proposition uncertain, to reject absolutely any unproved presuppositions, however self-evident they may be. We already find this requirement clearly expressed in Plato and Aristotle. For Plato, even “right opinion” that cannot be confirmed by proof is not “knowledge,” “for how could something unproved be knowledge?” But neither can it be called “lack of knowledge.” For Aristotle, “knowledge” is nothing else but “proved possession, hesis apodeiktikē, whence comes the vert term “apodeictic.”

It will be objected, however, that the latter proposition, i.e., the acceptance of only proved propositions an the sweeping away of everything else, is itself unproved. By introducing this proposition, does not the skeptic use the same sort of unproved presupposition as the one he condemned when the dogmatist used it? No. It is only an analytical expression of the essential striving of the philosopher, of his love of the Truth. Love of the Truth demands precisely truth, nothing else. The uncertain does not have to be the sought-for truth. It may be untruth, and therefore the lover of Truth must necessarily take care that he does not accept untruth under the guise of self-evidence. But precisely this kind of doubtful character distinguishes self-evidence. Self-evidence is the obtuse primary thing, which is not grounded further. And since self-evidence is unprovable, the philosopher falls into aporia, into a difficult position. The only thing that he could accept is self-evidence, but it too he cannot accept. And not being able to state a certain judgment, he is fated epechein, to delay with the judgment, to refrain from judgment. Epoche or the state of refraining from all statement, suspense of all judgment, is the last word of skepticism.

But what is epoche as a state of the soul? Is it “ataraxy, or imperturbability,” that profound tranquility of the spirit which has refused all statements, all judgments, that meekness and quietude about which the ancient skeptics dreamt? Or is it something else? Let us see.

And further, does one who has decided on ataraxy really become peaceful and tranquil like Pyrrho, the same Pyrrho in whom skeptics of all ages have seen their patron and almost a saint? Or is it that the enchanting image of this great skeptic has its roots not in the theoretical search for truth but in something else, in something that skepticism has not succeeded in touching? Let us see.

Expressed in words, epoche comes down the following two-part thesis:

I do not affirm anything.

I also do not affirm the fact that I do not affirm anything.

This two-part thesis is proved by a proposition established earlier: “Every unproved proposition is uncertain.” And the latter is the opposite side of love of the Truth.

If this is the case, I do not have any proved proposition; I do not affirm anything. But having just stated what I have stated, I must also remove this proposition, for it too is unproved. It we open up the first half of the thesis, it will have the form of a two-part judgment:

I affirm that I do not affirm anything (A’);

I do not affirm that I do not affirm anything (A”).

Now, as it turns out, we are obviously violating the law of identity by stating contradictory predicates about one and the same subject, about its affirmation, A, in one and the same connection. But that is not all.

Both parts of the thesis are an affirmative. The first is the affirmation of an affirmation, while the second is an affirmation of a nonaffirmation. The same process in inevitably applied to each. Thus, we obtain:

I affirm (A₁’);

I do not affirm (A₂’).

I affirm (A₁”);

I do not affirm (A₂”).

In the same way, the process will go further and further. Each new link will double the number of mutually contradictory propositions. The series goes toward infinity, and sooner or later, we are compelled to interrupt the process of doubling, in order to fix in immobility, like a frozen grimace, this obvious violation of the law of identity. We then get a powerful contradiction, i.e., at the same time we get:

A is A;

A is not A.

Not being in a position to harmonize actively these two parts of one proposition, we are compelled passively to surrender to contradictions that rip apart the consciousness. In affirming one thing, we are compelled at the same moment to affirm the opposite. In affirming the latter, we at once turn to the former. In the same way that an object is accompanied by a shadow, every affirmation is accompanied by the excruciating desire for the opposite affirmation. After having inwardly said “yes” to ourselves, we say “no” at the same moment. But the earlier “no” longs for “yes.” “Yes” and “no” are inseparable. Doubt, in the sense of uncertainty, is far away. Absolute doubt has now begun. This is doubt at the total impossibility of affirming anything at all, even of affirming its own rejection of affirmation. Processing stage by stage, manifesting the idea that inheres in it in nuce [as in a nut or seed], skepticism reaches its own negation but cannot leap across this negation. And so, it becomes an infinitely excruciating torment, an agony of the spirit. To clarify this state, let us imagine a drowning man who is attempting to grab hold of a polished sheer cliff face. He claws at the cliff with his fingernails, loses hold, claws at it again, and, crazed, catches at it again and again. Or let us imagine a bear that attempts to push aside a log suspended in front of a beehive. The greater the inner fury, the sweeter the honey seems.

Such also is the state of the consistent skeptic. What we see is not even affirmation and negation, but insane convulsions, a furious marching in place, a tossing from side to side, a kind of inarticulate philosophical howl. The result of abstention from judgment, absolute epoche, not as a tranquil and dispassionate refusal of judgment but as a concealed inner pain, a pain that clenches its teeth and strains every muscle in an effort not to scream and not to let out a completely insane howl.

To be sure, this is not ataraxy. No, this is the most furious of tortures, pulling at the hidden fibers of one’s entire being. It is a pyrrhonic, truly fiery (Gk. pyr = fire) torment. Molten lava flows in the veins, and a dark flame penetrates the marrow of the bones. At the same time, the deadening cold of absolute solitude and perdition turns the consciousness into a block of ice. There are no words. There are not even any moans to moan out—if only into the air—a million torments. The tongue refuses to obey. As Scripture says: “my tongue cleaveth to my jaws” (Ps: 22:15; cf Ps. 137:6, Lam. 4:4, Eze. 3:26). There is no help, no means to stop the torture, for the consuming fire of Prometheus comes from within, for the true focus of the fiery agony is the very center of the philosopher, his “I,” which struggles to attain unconditional knowledge.

I do not have truth but the idea of truth burns me. I do not have the evidence to affirm that there is Truth in general and that I will attain the Truth. My making such an affirmation I would renounce the thirst for the absolute, because I would accept something unproved. Nevertheless, the idea of Truth lives in me like a “devouring fire,” and the secret yearning to meet Truth face to face makes my tongue cleave to my jaws. It is this yearning that seethes and bubbles in my veins like a flaming stream. If there were no hope, the torture too would cease. Consciousness would then return to philosophical philistinism, to the domain of the conditional. For this fiery hope of Truth melts with its black flame every conditional truth, every uncertain proposition. It is also uncertain whether I yearn for Truth. Perhaps that too only seems. But perhaps this very seeming is not seeming?

In asking myself this last question, I enter into the last circle of the skeptical hell, into the place where the very meaning of words is lost. Words cease to be fixed; they fly out of their nests. Everything turns into everything else. Every word-combination is completely equivalent to every other, and any word can change places with any other. Here, the mind loses itself, is lost in a formless, chaotic abyss. Here, delirium and senselessness lurk.

But this maximally skeptical doubt is possible only as an unstable equilibrium, as the limit of absolute dementia, for what is dementia but de-ment-ia, or mindlessness, the experience of the non-substantiality, the non-supportedness, of the mind. When this doubt is experienced, it is carefully hidden from others. And after being experienced, it is remember with great reluctance. From the outside it is almost impossible to understand what this is. Delirious chaos pours forth through this ultimate limit of reason, and the mind is deadened with an all-penetrating cold. Here, behind a thin barrier, spiritual death begins. Therefore, the state of ultimate skepticism is possible only for the blink of an eye, followed by the return to the fiery torment of Pyrrho, to epoche, or by the plunge into the pitch-black night of despair, whence there is no escape and where they very thirst for Truth disappears. From the sublime to the ridiculous is a single step, and this is precisely a step that takes one away from the ground of reason.

Thus, the way of skepticism also leads to nothing.

We demand certainty, and this demand is expressed in the decision to accept nothing without proof. But at the same time the very proposition “not to accept anything without proof” must be proved. Let us see, however, if we have made an dogmatic assumptions in the forgoing discussion. Let us turn back.

We have sought a proposition that would be absolutely proven. But on the path of our seeking, a certain feature of this sought-for proposition which remains unproved crept in. Namely, this sought-for absolutely proved proposition has for some reason been recognized in advance as first in its provenness, as that from which all positive work begins. There is no doubt that this very affirmation of the primacy of an absolutely proved judgment is, since it is unproved, a dogmatic presupposition. For it is possible that the sought-for proposition will be in our hands, though not as the first, but as the result of other propositions, uncertain ones.

“From the uncertain the certain cannot be derived.” This indisputably dogmatic presupposition lies at the base of the affirmation of the primacy of the certain Truth. Yes, it is dogmatic, for it is nowhere proved.

Thus, again rejecting the path we have taken, we reject the dogmatic presupposition we have found and say: We do not know whether or not a certain proposition exists; but if it does exist, we do not know whether or not it is first. Moreover, that “we do not know” we also do not know, and so on, as before. Further our epoche will begin, and it will be of a kind similar to that encountered before. But our present state will be somewhat new. We do not know whether or not the Truth exists. But if it exists, we do not know if reason can lead to it. And if reason can lead to it, we do not know how reason could lead to it and where reason could meet it. But, in spite of all this, we say to ourselves: If the Truth exists, it could be sought. Perhaps we could find it by taking some road at random, and then it would perhaps announce itself as such, as the Truth.

But why do I speak this way? Where is the ground for my affirmation? There is no ground. Therefore, given the demand that my proposition be proved, I now remove this presupposition from the agenda and return to the epochē with the affirmation: “Perhaps this is true or perhaps the opposite is true.” One I am asked for an answer to the question, “Is this so? I say, “It is not so.” But if I am asked decisively, “Is this not so?” I say, “It is so.” I ask; I do not affirm; and what I put into my words is something not at all logical. What is this something? It is the tone of hope but not the logical expression of hope. And from this tone there follows only the fact that I will nevertheless try to make the proposed unjustified, but not condemned, attempt to find the Truth. If I am asked about grounds, I will curl up in myself like a snail. I see that I am threatened either by the insanity of abstaining from the search or by the—perhaps—vain labor of attempts: work in the full consciousness that it is ungrounded, and that justification is conceivable only as an accident, or rather as a gift, as gratia quae gratis datur. Does not St. Seraphim of Sarov speak of the same thing when he says, “If a man, out of love for God, does not overmuch concern himself with himself, that is a wise hope”? In conformity with St. Seraphim’s words, I do not want to “concern myself overmuch with myself,” with my rational mind. That is, I want to hope.

Thus I grope along, all the while remembering that my steps do not have any significance. At my own risk, on the off chance, I am attempting to grow something, being guided not by philosophical skepticism but by my own feeling. And for a time I will refrain from turning this feeling into ash with pyrrhonian lava. I cherish a secret hope—hope for a miracle. Perhaps the flow of lava will move aside before my shoot, and the plant will turn out to be a burning bush. But this, I keep to myself. And in keeping to myself, I accept the word of the kathisma which I have heard a thousand times in church but which has only now for some reason surfaced in my consciousness: “Those who seek God shall not be deprived of any good.” Yes, those who seek, those who thirst. The verse does not says “those who have,” and it would be superfluous to say this, for it goes without saying that those who have God, the Original Source of all good, will not be deprived of any particular good. And perhaps it would be incorrect to say this, for can anyone say that he has God wholly and that he is therefore not one of those who seek? But it is precisely those who seek God who will not be deprived of any good. Seeking is affirmed by the Church as non-deprivation. It turns out that those who have not are identical to those who have. But although this equality is as yet unproved, it has become dear to my soul. And since I do not have anything, why should I not submit myself to this power of God’s words.

Thus, I enter into a new domain, that of probabilism—under the necessary condition, however, that my entry into this domain be only a trial, only an experiment. The true homeland is still epoche, But if I resisted my presentiment and did not desire to leave epoche, it would still be necessary to justify my stubbornness, which I could not do, just as now I cannot justify my leaving epoche. Neither for the one not for the other do I have any justification. But, practically, of course, it is more natural to search for a path, even if only hoping for a miracle, than to sit in place in despair. But in order to search it is necessary to be outside of one’s rational mind. Here again, a question arises: By what right do we go beyond our rational mind? By the right that is given to us by the rational mind itself: It compels us to it. Indeed, what remains to be done when the rational mind refuses to serve?

I want to form a problematic construction, keeping in mind that perhaps it will accidentally turn out to be certain. “Turn out to be!” With these words, I have carried my search from the ground of speculation to the domain of experience, of actual perception, but of experience and perception which must be united with inner reasonableness as well.

What are the formal, speculative conditions that would be satisfied if such experience actually arose? In other words, what judgments would we necessarily form concerning this experience (let me emphasize once again that we do not have this experience):

These judgments are as follows:

(1) The absolute Truth exists, i.e., it is unconditional reality.

(2) The absolute Truth is knowable, i.e., it is unconditional reasonableness.

(3) The absolute Truth is given as a fact, i.e., it is a finite intuition, but it is absolutely proven, i.e., it has the structure of infinite discursion.

Moreover, the third proposition, after analysis, implies two others. In fact, “Truth is intuition.” This means that it exists. Further, “Truth is discursion.” That means that it is knowable. For intuitiveness is the de facto givenness of existence, whereas discursiveness is the ideal possibility of knowing.

This means that all our attention is concentrated on a proposition that is dual in content but one in idea: “Truth is intuition; Truth is discursion.” Or more simply:

“TRUTH IS INTUITION-DISCURSION”

Truth is intuition that is provable, i.e., discursive. In order to be discursive, intuition must be intuition that is not blind, not obtusely limited. In must be intuition that tends to infinity. It must be speaking, reasonable, intuition, as it were. In order to be intuitive, discursion must not lose itself in boundlessness. It must be not only possible but also real, actual.

Discursive intuition must contain a synthesized infinite series of its own grounds, whereas intuitive discursion must synthesize its whole infinite series of grounds into a finitude, a unity, a unit. Discursive intuition is intuition that is differentiated to infinity, whereas intuitive discursion is discursion that is integrated to unity.

Thus, if the Truth exists, it is real reasonableness and reasonable reality. It is finite infinity and infinite finitude or—to use a mathematic expression—actual infinity, the Infinite conceived as integral Unity, as one Subject complete in itself. But complete in itself, Truth carries in itself the whole fullness of the infinite series of its grounds, the depth of its perspective. The Truth is a sun that illuminates both itself and the whole universe. Its abyss is the abyss of power, not of nothingness. The Truth is immobile motion and moving immobility. It is the unity of opposites, coincidentia oppositorum.

If that is the case, skepticism in fact cannot destroy truth and truth is in fact “stronger than everything.” The Truth always gives to skepticism a justification of itself. The Truth is always “answerable.” To every “why” there is an answer, and all these answer are not given separately, are not lined to one another externally, but are woven into an integral, inwardly fused unity. A single moment of perception of the Truth gives the Truth with all its grounds (even if they have never been conceived separately by anyone anywhere!). The blink of an eye gives the fullness of knowledge.

Such is absolute Truth, if it exists. In it, the law of identity must find its justification and ground. Abiding above all ground that is external to it, above the law of identity, the Truth grounds and proves this law. The Truth contains the explanation of why being is not subject to this law.

A probabilistically presuppositions construction leads to the affirmation of Truth as a self-proving Subject, a Subject qui per se ipsum concipitur et demonstrator (that is conceived and proved through itself), a Subject that is absolute Lord of itself, that is master over the infinite serious of all its grounds, which are synthesized into a unity and even into a unit. We cannot concretely conceive such a Subject, for we cannot synthesize an infinite series in its entirety; on the path of successive syntheses we will alway see only the finite and conditional. Adding a finite number to a finite number an arbitrary number of times, we get nothing but a finite number. Ascending higher and higher into the mountains (to use Kant’s image), we would hope in vain to touch the sky with our hand. And it is insane to count on the Tower of Babel. In the same way, all of our efforts will always yield only what is in the process of being synthesized, but never what is already synthesized. An infinite Unit is transcendental to human attainments.

If, in consciousness, we had a real perception of such a self-proving Subject, this perception would be precisely the answer to the question of skepticism and would therefore destroy epoche. If epoche is resolvable at all, it is so only by this kind of destruction, by sovereign satisfaction, as it were. But epoche definitely cannot be merely avoided or eliminated. The attempt to disdain epoche is inevitable a logical trick, nothing more. And in the vain attempt to perform this trick, all dogmatic systems, not excluding Kant’s, come to ruin.

In fact, if the condition of intuitive concreteness is not satisfied, the Truth will be only on empty possibility. If the condition of reasonable discursiveness is not satisfied, the Truth will be no more than a blind givenness. Only a finite synthesis of infinity, a synthesis realized independently of us, can give us a reasonable givenness or, in other words, the self-proving Subject.

Having in itself all the grounds of itself and all the manifestation of itself to us, having in itself all the grounds of its reasonableness and its givenness, this Subject is self-grounded not only in the order of reasonableness but also in the order of givenness. It is causa sui both in essence and in existence, i.e., it not only per se ipsum concipitur et demonstrator but also per se est. It “is through itself and is known through itself.” This was understood well by the scholastics.

Thus according to the definition of Anselm of Canterbury, God is “per se ipsum ens,” “ens per se.” Thomas Aquinas remarks that God’s nature “per se necesse esse,” for it is “prima causa essendi, non habens ab alio esse.” Here is a more precise definition of this “per se“: “per se ens est, quod separatim abseque adminicolo alterius existit, seu quod non est in subjecto inhaesionis: quod non est hoc modo per se accidens.”

This conception of God as having His being and reason in Himself run through scholastic philosophy like a scarlet thread an finds its extreme but one-sided application in Spinoza. According to the third definition in Spinoza’s Ethics, which leaves its particular imprint on his entire system, a substance is precisely that which has its being and reason in itself: “Per substantium intelligo id, quod in se est et per se concipitur.”

The self-proving Subject! Formally, we can affirm that this “Infinite Unit,” explains everything, for to give an explanation of something is, first of all, to show how it does not contradict the law of identity and, secondly, to show how the givenness of the law of identity does not contradict the possibility of the grounding of this law.

A new question arises, however. Let us suppose that the infinity of the series grounds that is synthesized into a finite intuition has appeared in our perception as a kind of revelation. Let that be the case. But how precisely can this intuition form a basis for the law of identity which all its violations?

First of all, how are the multiplicity of coexistence (disharmony, otherness) and the multiplicity of succession (change, motion) possible? In other words, how is it that a spatiotemporal multiplicity does not violate identity?

It does not violate identity only if a multitude of elements is absolutely synthesized in the Truth, so that “the other”—both in the order of coexistence and in the order of succession—is at the same time “not other” sub specie aeternitatis: if the heterotēs, the differentness, the alienness of the “other” is only an expression and disclosure of the tautotēs, of the identity of “this one.”

If “another” moment of time does not destroy and devour “this” moment, but is both “another” moment and “this” moment at the same time, if the “new,” revealed as the new, is the “old” in its eternity; if the inner structure of the eternal , of “this” and “the other,” of the “new” and the “old” in their real unity is such that “this” must appear outside the “other” and the “old” must appear before the “new”; if the “other” and the “new” is such not through itself but thought “this” and “the old” and “this” and “the old” is what in is not through itself but through the “other” and the “new”; if, finally, each element of being is only a term of a substantial relationship, a relationship-substance, then the law of identity, eternally violated, is eternally restored by its very violation.

This last proposition gives an answer to a very old questions: How is it possible that every A is A? In this case, from the very law of identity there flows a spring that destroys identity, but this destruction of identity is also the power and force of the eternal restoration and renewal of identity. Identity, dead as fact, can be and necessarily is alive as act. The law of identity will then not be a universal law of superficial being, as it were, but the surface of very deep being, not a geometrical figure but the external aspect of a depth of life inaccessible to the rational mind. And in this life this law can have its root and justification. The law of identity, blind in its givenness, can be reasonable in its createdness, in its eternal being-created. Fleshly, dead, and deadening in its statics, this law can be spiritual, living, and life-giving in its dynamics. To the question: Why is A A? we answer, A is A because, eternally being not-A, in this not-A, it finds its affirmation as A. More precisely, A is A because it is not-A. Not being equal to A, i.e., to itself, it is always being established in the eternal order of being by virtue of not-A as A. This will be discussed in greater detail later.

Thus, the law of identity will receive its grounding not in its lower, rational form, but in its higher reasonable form.

Instead of an empty, dead, formal self-identity A = A, in virtue of which A should selfishly, self-assertively, egotistically exclude every not-A, we get a real self-identity of A, full of content and life, a self-identity that eternally rejects itself and that eternally receives itself in its self-rejection. If, in this first A is A (A = A) because of the exclusion from it of everything (and of itself in its concreteness!), now A is A through the affirmation of itself as not-A, though the assimilation of everything and the likening of everything to itself.

From this it is clear what the nature of the self-Proving subject is and what constitutes its self-provenness, if this Subject exists at all.

The Subject is such that it is A and not-A. For the sake of clarity, let us designate not-A through B. What is B? B is B, but it would itself be a blind B if it were not also not-B. What is not-B? If it is merely A, then A and B would be identical. A, being A and B, would be only a simple naked A, just like B. (As we shall see, in heresiology this corresponds to modalism, Sabellianism, etc.) In order for there not to be the simple tautology “A = A,” in order for there to be a real equality of “A is A, for A is not-A,” it is necessary that B itself be a reality, i.e. that B at once be B and not-B. Through C the circle can be close, for in its “other,” in not-C, A finds itself as A. In B ceasing to be A, A receives itself mediately from another, but not from the one with which it is equated, i.e., from C. And here it receives itself as already “proved,” already established. The same thing goes for each of the subjects A, B, C of the triple relationship.

The self-provenness and self-groundedness of the Subject of the Truth, I, is the relation to He through Thou. Through Thou the subjective I becomes the objective He, and, in the latter, I has its affirmation, its objectivity as I. He is I revealed. The Truth contemplates Itself through Itself in Itself. But each moment of this absolute act is itself absolute, is itself Truth. Truth is the contemplation of Oneself through Another in a Third: Father, Son, and Spirit. Such is the metaphysical definition of the “essence” (ousia) of the self-proving Subject, which is, as is evident, a substantial relationship. The Subject of the Truth is a relationship of the Three, but this is a relationship that is a substance, a relationship-substance. The Subject of the Truth is a Relationship of Three. And since a concrete relationship is, in general, a system of life-acts, is this case an infinite system of acts synthesized into a unit or an infinite unitary act, we can affirm that the ousia of the Truth is the Infinite act of Three in Unity. Later we will explain this infinite act more concretely.

[[[ EVE NOTE: Aristotle had already noted the triadic structure of the Unmoved Mover. It was the act of noēsis, thought or apprehension, and yet it was a mind, nous, which existed in its act of thinking or contemplating the highest perfection, itself, so, thinking. The Unmoved Mover is nous noēsis-ing nous or thought thinking thought, or perhaps, thinking thinking thinking, and since its act is also to be, it could be called being being being. Not the Christian trinity, but it is interesting that Aristotle worked out God needs to be a threefold in some sense. ]]]

But what is each of the “Three” in relation to the infinite act-substance?

What is real is not the same thing as the whole Subject, and what is real is precisely the same thing as the whole Subject. In view of the necessity of further discussion, we will call it “hypostasis” where it is “not the same thing.” Earlier we applied the term “essence” (ousia) to designate it as precisely the same thing.

The Truth is therefore one essence with three hypostases. Not three essences, but one; not one hypostasis, but three. But, despite all this, hypostasis and essence are one and the same. Expressing myself somewhat imprecisely, I will say: a hypostasis is an absolute person.” But the question arises: “What constitutes a person if not an essence?” And also: “Is essence given except in a person?” Nevertheless, all of the foregoing establishes that there is not one hypostasis, but three, although essence is concretely one. Therefore, numerically, there is one Subject of the Truth, not three.

“Our holy and blessed fathers,” writes Abba Thalassius, “recognize as trihypostatic the one substance of Divinity just as they confess the Holy Trinity as consubstantial. The Unity, extending, according to them, to the Trinity, remains a Unity; and the Trinity, collecting itself into a Unity, remains a Trinity. And this is miraculous. They thus preserve as immutable and unalterable the property of the hypostases, while preserving the commonality of the substance, i.e., Divinity, as indivisible. We confess Unity in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity, divided individuality, and joined divisibility.”

But I will be asked: Why are there precisely three hypostases? I speak of the number “three” as immanent to the Truth, as inwardly inseparable from the Truth. There cannot be fewer than three, for only three hypostases eternally make one another what they eternally are. Only in the unity of Three does each hypostasis receive an absolute affirmation, which establishes this hypostasis as such. Outside the Three, there is not one, there is no Subject of the Truth. But more than three? Yes, there can be more than three—through the acceptance of new hypostases into the interior of the life of the Three. But these new hypostases are not members which support the Subject of the Truth, and therefore they are not inwardly necessary for the Subject’s absoluteness. They are conditional hypostases, which can be but do not have to be in the Subject of the Truth. Therefore, they cannot be called hypostases in the strict sense, and it is better call them deified persons, etc. But there is also another side which we have neglected up to now (but which later we will examine carefully): In the absolute Unity of the Three, there is no “order,” no sequence. In the three hypostases, each is immediately next to each, and the relationship of two can only be mediated by the third. Primacy is absolutely unthinkable among them. But every fourth hypostasis introduces into the relation to itself of the first three so order or other, thus through itself placing the hypostases into an unequal activity in relation to itself, as the fourth hypostasis. From this one sees that with the fourth hypostasis there begins a completely new essence, whereas the first three were of one essence.

In other words, the Trinity can be without a fourth hypostasis, whereas a fourth cannot be independent. This the general meaning of the number three in the Trinity.