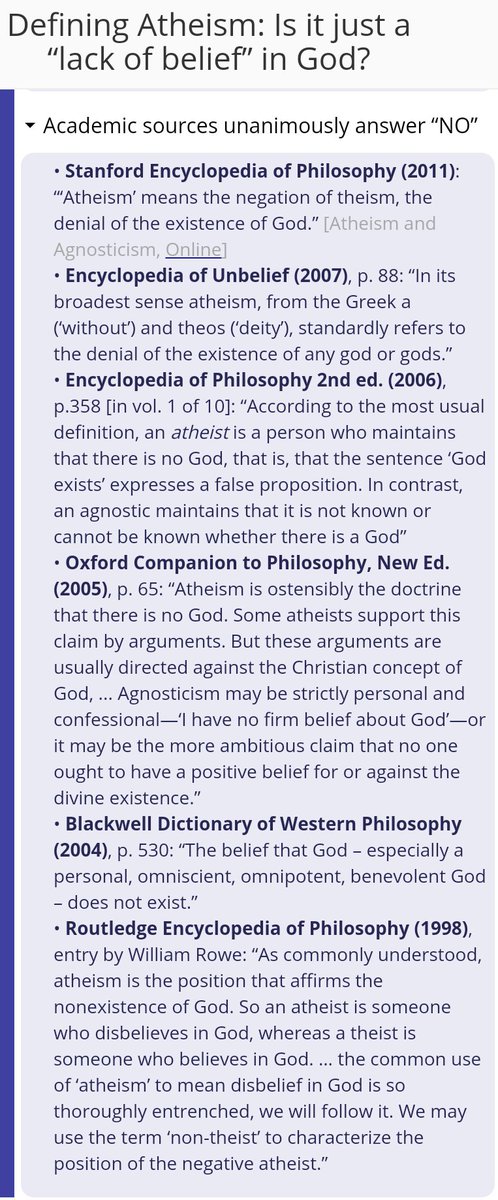

NOTE: I didn’t make this chart. I found it on Twitter, and thought it worth archiving here. It has been noted that this “no” may not be entirely unanimous, but it is nevertheless highly significant that the “lack of belief” definition of atheism has really made very little headway among professional scholars, except when they note it as a variant definition, which is highly contentious, and thus usually used only by those who are ideologically motivated in their arguments.

Eve, may I ask: What is your opinion on Graham Oppy?

LikeLike

Not high. His “best argument against God” seems entirely question-begging to me. It seems to run: “On the assumption that naturalism is true, then naturalism is the best explanation for all phenomena, which are all, of course, natural.”

That’s really not much of an argument. He systematically either denies phenomena that naturalism cannot explain or he tries to write blank checks on the grounds that naturalism will, eventually—no, really!—explain things it seems impossible in principle that naturalism could explain. In other words, he seems to have a kind of blind faith that naturalism is true, so that there are no non-natural phenomena nor phenomena that aren’t natural. It’s tautological if it starts from naturalism as a presumption, so it fails as an argument. And if naturalism is not presupposed, then the argument fails.

LikeLike

What would these phenomena be that are unable to be explained by/within naturalism? The existence of nature itself?

LikeLike

Any evaluative or normative dimension (ethics, aesthetics) is extremely hard (probably impossible) to explain (away) naturalistically.

So are maths and logics.

So are mental phenomena.

(Don’t be fooled by naturalists fooling themselves that they are about to naturalistically explain (away) all of the above. They are either sneaking some evaluatitve dimension in by the back door or they are stoutly denying phenomena others find both basic and obvious.)

And while I am far from an expert on theistic arguments, the first cause argument and the argument from contingency both seem to have such weak assumptions that the naturalist would be hard pressed not to share them. The first cause argument might need a stronger notion of causation than some (humean) naturalists might want to adopt (although I think they *should* adopt a stronger than humean notion of causation, it’s all they have to keep their world together and then they are only one step away from a first cause argument).

But the argument from contingency needs basically only PSR and some distinction between contingent and non-contingent entities (or things that have to be explained and things that need not be explained). As Eve and others have pointed out repeatedly, if one denies PSR one has to wonder why one should bother to explain anything at all and why not stop at some particular point rather than another. This runs against core ideas of scientific inquiry the naturalists shares.

The naturalists basically have to posit that the universe as a whole is necessary which seems clearly special pleading because the universe has all the marks of contingency (changes, does not explain itself, seems not obviously necessarily existent). I don’t see any (good) argument from science why the universe should be necessary despite appearing contingent.

I think that if one posits a universe that could really fulfill that role naturalism would have to be changed into some kind of Spinozism. Again, I am not an expert but I tend to the position that the plausible alternatives to Theism are closer to Spinozism (God=Nature=Substance) or some kind of Absolute Idealism than to naturalism.

LikeLike

I’m sorry I’m bothering you again, Eve, but I recently heard the following questions, and I’d like to hear someones opinion/answers to it:

Was there a phase of “time”, for a lack of a better word, when God was not the Creator? How so, If Creation is a definition of Gods being?

And If he changed, how would that be possible, given that he is the Unchanging one?

And:

Why did God create the world If he is the Absolute, Perfect, and Complete? He does not need anything. But If God does nothing pointless, then he did indeed miss something. I guess this one boils down to that God, the perfect being, would not create anything.

Thoughts?

LikeLike

As what you would probably describe as a “militant atheist”, I find myself frequently criticizing these “lackers” as intellectually incoherent, and not without some success. I saw your post on the etymology of the word “atheist” and agree entirely; in fact I’ve been pointing this out for some time now.

Still, these intellectual habits die hard – one can’t call them “old” after all. It’s a tactic for evading engagement, rather than meeting it head on. Rather like, I should add, proposing that the capital “G” in god yields a specific denotation, even in a generally western cultural context. In my view, both are attempts at claiming a specific conclusion without accepting the intellectual responsibility of arguing for it.

I hope you don’t mind me saying so, and I look forward to reading more of your posts.

LikeLike

All Western languages for millennia have distinguished God from gods or a god. The capital G does in fact mark a different denotation, one roughly analogous to das Sein and seiende in German, which in Heidegger scholarship are often rendered as Being and beings (respectively). Being is not a being, and to attempt to conceptualize Being as a being is to commit the grossest kind of category mistake. The situation is the relevantly similar (although not identical) with God and a god. Another analogy, again not the same as either of the previous two, but similar, would be the attempt to conceptualize Time as an entity that exists at some time or Space as an entity that exists somewhere in space. It is manifestly nonsensical to ask “When is time?” or “Where is space?” as if “time” were an entity that could be at some point in time, or space an entity that is located in space. Writing God, Being, Time, and Space with capitals is a helpful semantic device to avoid these elementary confusions.

There is no claim to a specific conclusion in speaking about God rather than a god. I, and almost all other theists, are simply not talking about gods, and to claim that we are, is both a category mistake and intellectually dishonest. There is no conclusion being drawn when the claim is WHAT I AM TALKING ABOUT that you or anyone else could confute.

LikeLike

It’s not clear to me why you decided to object to my claim that the capitalized “God” yields a specific denotation by responding with “[ there ] is no claim to a specific conclusion in speaking about God rather than god,” since this is literally a restatement of my point. As to there being any category mistake in denying the capital, well I’m sure you’ll agree that just as any pronoun is categorically a kind of noun, so too is any God a kind of god, just as Time – to be at all meaningful as a reference and signifier – is a kind of time. Or do you not mean that God is a specific god, even if the only example, of that category?

Oh but you can’t mean that, I see now, as this would imply that God is in fact a “claim to a specific conclusion”. But if God is not a god, and if the god is not God, then to what is God referring?

In any case, the pronominal casing of the grammatical objective hardly seems a means adding specificity or clarity to the claim, and except by implication can offer no denotative reference at all. Perhaps that’s the purpose for your unnecessary all-caps point that “God” simply refers to whatever it is you say you’re talking about. But if this is not a “claim to a specific conclusion”, i.e. that “God” is a specific entity denoted by a set of characteristics unique to it, then I wonder what it is that you think you are talking about.

LikeLike

Erm, really?

You wrote:

Eve responded:

, which is not a “literal restatement” but an explicit denial of your point. You can surely distinguish between the denotation and any conclusions about that denotation, for your own point relied on that distinction.

Time is a kind of time? If you can really keep a straight face while typing such nonsense, it is no wonder that you think that God must be a god. Perhaps reading Eve’s earlier post would help: https://lastedenblog.wordpress.com/2017/05/20/intellectually-dishonest-or-deficient-atheists/

LikeLike

Thanks for trying to clarify this for me. I can understand the confusion here, since when Eve responded to my point about asserting a “specific denotation” by mentioning a “different denotation”, she raises the question of whether she is responding to my point at all.

I take Eve’s response to mean that “God” has a denotation which which is different from that of “god”, but which differs in some important respect in terms of specification. So it seems to me the question is whether or not one can refer to “God” without a specific reference, as one can to “god”, anf if so, what meaningful difference there is between them.

Since all Western languages indicate by capitalization of the first letter of a noun the presence of a pronoun, which in fact does point to a specific referent, I find the idea that “God” does not do so problematic from the standpoint of the “category mistake” and dishonesty charges. Eve here claims that in context of Heidegger scholarship such language is philosophically and formally defined, yet without offering a meaningful denotation of “God” in this context either.

Now philosophically formal definitions being what they are, I certainly don’t begrudge her this ambiguity. I’m sure you can understand, however, my confusion. I have claimed this use of the spelling “God” seeks to assert a specific denotation without actually establishing it, and Eve seems to respond with an illustration of just that. However, in explicitly pointing out that “God” does not make a “specific conclusion”, she is in fact agreeing with me that the term does not establish any such meaning.

The problem, of course, is this less than specific language about what “God” is, while still claiming it does in fact refer to something. This necessitates awkward and esoteric analogies to “time” and “Time”, for example, on her part, and given the example I’m afraid I could do no better. Thus she appears to restate my claim that “God” does not refer to anything specific, all while apparently arguing it does.

I hope that helps you to understand my confusion here, and that it didn’t too badly tax your patience. I hope you’ll be able to clear things up for me.

LikeLike

Yes, exactly. I suggest you start by reading these two posts:

The two words “God” and “god” simply do not mean the same thing, nor is there even much resemblance between their referents.

The denotation of “God” assumes nothing beyond itself. When St. Thomas asks “Does God exist?”, the question does not imply a particular answer, although there will, in fact, be a particular answer and even a necessary one. This in no way excuses anyone from doing intellectual work.

LikeLike

But of course, no denotation assumes anything beyond itself. That’s why Eve does indeed draw rather profound conclusions from the denotation “God”:

What Eve meant to say, I presume, is that the denotation “God” does not refer to Allah, or Yahweh, or Zeus. Instead, this “God” refers to something which necessarily exists, assuming the truth of the cosmological argument, and demanding that I do so as well in order to even speak of “God’s” existence. And this is of course exactly what I criticized earlier. It is nothing more than an attempt to ensure the desired conclusion by demanding that one accept the premise of what this “God” is.

So in fact what Eve is demanding is that I, as an atheist, must accept that such a god exists to be honest in debating whether or not that god exists.

LikeLike

Everything up until the “Indeed,” JUST IS the denotation. THAT is what we classical theists are talking about when we are talking about God. If you want to demonstrate anything about God, it has to be ABOUT THAT. If you continue to talk about gods, you are simply talking about something else, and everything you say will be totally irrelevant to the only point at issue: the being and nature of God.

Both “Yahweh” and “Allah” are words that came to be used to refer to God rather than a god. To a lesser extent, this happened with “Zeus” among some Greek philosophers—”Zeus” is sounded as “Sdeus” after all, and is cognate with the Latin “Deus,” or God. However, the use of Zeus as a proper name for a god was generally too strong to be replaced. Thus one has at best aphorisms such as that of Heracleitus of Ephesus, “The Wise is One only, both willing and unwilling to be called by the name of Zeus.”

Xenophanes is known for the observations that “Men create gods in their own image” and “If animals could speak of gods, horses would speak of gods as horses, dogs as dogs, pigs as pigs” BUT ALSO “God in One, greater than gods or men, not like mortals in body or thought.” Xenophanes’ is very clearly making the very same distinction I am (and everyone who is not an ass does), namely, that gods are something other than God—gods are man-made, according to Xenophanes, and that seems reasonable enough to me. God, however, is another matter.

The Greek thinkers worked out fairly early that gods, if there are any, aren’t particularly important—but that God is fundamental question. The Hebrews did not work this out, but as it happens, had the distinction of having God Himself teach this to them.

LikeLike

So your denoted “God” has, as one of its characteristics, that it is the necessary entity for all of creation, and that a la the cosmological argument, “God” necessarily exists. If therefore I argue that “God” doesn’t exist, will you then accuse me of not having referred to what you’re talking about? If not, and you are merely and reasonably agreeing that your claim is of a god which is also “God”, for which its divine hierarchy may or may not include lesser divine creatures, then why the insistence on my referring to “God” as a pronoun?

The latter condition is merely a demand that the atheist should actually address the claim that the theist offers, in which case this argument about “God” vs. gods is beside the point, or at best an illustration. This is of course so patently obvious that one wonders why it would need to be stated at all. I’m sure that there are atheists out there who refuse to address the claims they purport to refute, just as there are theists who do the same. But surely we do not address reasonable expectations to the unreasonable.

So I am left wondering how your argument can be disambiguated from the first of the above interpretations. If I refute the cosmological argument, whether Plato’s or Aristotle’s prime mover or the Kalam variation, will you agree that I have refuted the existence of “God”, or will you claim I have been talking about something else all along?

The ancient Greeks did not, as it happens, agree that “‘God’ is the fundamental question”. Xenophanes himself established that no answer to that “question” was available to humans:

LikeLike

What term would you use for someone who lacks belief in any gods, without necessarily asserting that none of them exist?

I suppose the term “agnostic” might be shanghaied into service, but I prefer to avoid it, since it has enough different meanings that without additional clarification, it doesn’t convey much useful information.

LikeLike

Which is why you would rather use the term “atheist” which, except for its dictionary definition, has enough different meanings that without additional clarification, it doesn’t convey much useful information?

LikeLike

Thanks, but that doesn’t answer my question: what’s a good term for someone who lacks belief in any gods (and may or may not assert the non-existence of any given deities)? That’s a pretty common stance, so there ought to be a word for it. What do you suggest?

LikeLike

Phew, I guess this right here is one reason for why philosophy of language exists. You have a 1000 people, and you have 1002 different meanings for the same word. However, atheist is most certainly not it. Agnosticism still seems to me the best option

LikeLike