“There Is No Evidence For God”

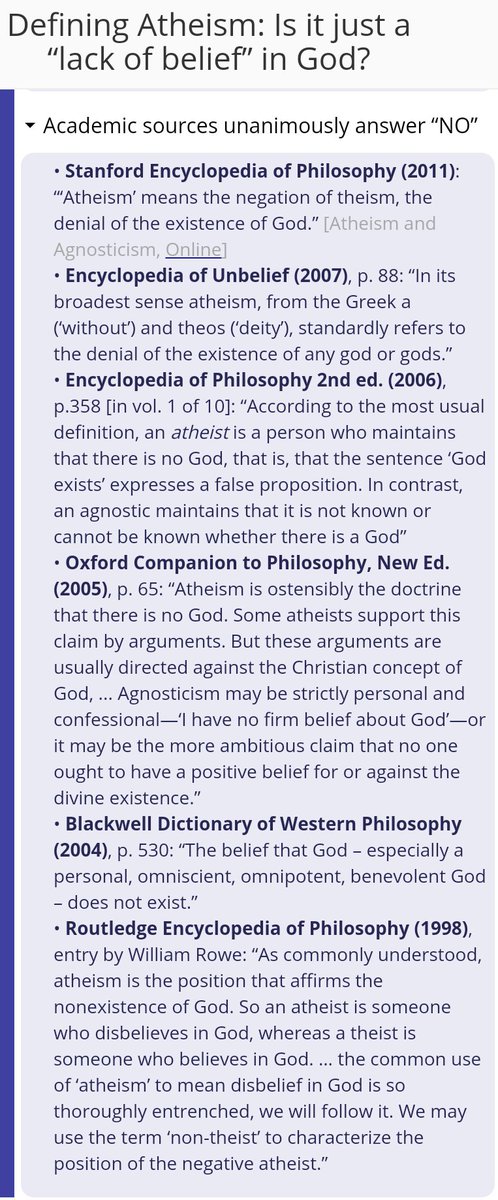

NOTE: I didn’t make this chart. I found it on Twitter, and thought it worth archiving here. It has been noted that this “no” may not be entirely unanimous, but it is nevertheless highly significant that the “lack of belief” definition of atheism has really made very little headway among professional scholars, except when they note it as a variant definition, which is highly contentious, and thus usually used only by those who are ideologically motivated in their arguments.

An atheist who goes by [theresidentskeptic] is one of many atheists who have demanded that the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy change its definition of atheism to their preferred one, namely, the dishonest “lack of belief” definition. Here’s how the SEoP’s definition reads:

And here is [theresidentskeptic]’s email and Stanford’s reply:

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Dear Stanford,

I am constantly having your definitions of atheism and agnosticism regurgitated to me by people who don’t seem to understand what they mean and your authoritative definition completely muddies the waters.

Your definition which can be seen at the the following link states:

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheis…sticism/#1

“‘Agnostic’ is more contextual than is ‘atheist’, as it can be used in a non-theological way, as when a cosmologist might say that she is agnostic about string theory, neither believing nor disbelieving it.”

I am forced to point out to you that agnosticism deals with knowledge claims, not claims of belief. Why are you conflating the two? A belief necessarily deals with a single claim; God exists is one claim; God does not exist is another claim- or String theory is true is one claim; string theory is not true is another claim.

A cosmologist who does not know if either position about string theory is true would be considered an agnostic. The cosmologist then disbelieves claim 1; string theory is true, therefore, for lack of a better term, is an atheist with respect to string theory. They do not necessarily believe that claim 2; string theory is false, is true.

Similarly, with respect to god claims, a person who does not know if either claim (god exists / god does not exist) is true would be an agnostic. The person who disbelieves claim 1; God exists is an atheist and this does not say anything about their acceptance that claim 2; god does not exist, is true.

I will use an analogy:

If I made the claim that there are an odd number of blades of grass in my front yard, would you believe me?

No, you wouldn’t unless I could substantiate that claim (if you are rational). Does that then mean you believe the opposite of that claim? That there are an even number of blades of grass in my front yard? No, you wouldn’t accept that claim either. With respect to your belief in the true dichotomy of the nature of the grass then, you are an atheist; you disbelieve claim 1; there are an odd number of blades of grass. If you don’t know which claim is true, you are an agnostic. The terms are not mutually exclusive.

With respect to god claims, I identify as an agnostic atheist; I do not know if a god exists or not, and I disbelieve the claim that a god does exist.

Gnostic: Of or relating to knowledge, especially esoteric mystical knowledge. –> Therefore it’s opposite, agnostic, relates to a lack of knowledge.

Theist: Belief in the existence of a god or gods, especially belief in one god as creator of the universe, intervening in it and sustaining a personal relation to his creatures –> Therefore it’s opposite, atheist, relates to a lack of belief in the existence of gods and not necessarily the belief in the opposite claim, that no gods exist.

Belief: an acceptance that a statement is true or that something exists

Source [for definitions]: Oxford English Dictionary*

Kindly update your definitions to reflect this.

Thank you.

Sincerely,

[theresidentskeptic]

*EVE NOTE: [theresidentskeptic] is being dishonest here: his definitions are from the Oxford Dictionary, not the Oxford English Dictionary or OED, which is an important distinction—the OD accepts and uses much looser standards than the OED. The OD is what you get from Google. The OED requires a hefty fee to access.

———————————-REPLY FROM STANFORD BELOW———————————-

Dear [theresidentskeptic]

Thank you for writing to us about the entry on atheism and agnosticism. We have received messages about this issue before and are continuing to consider whether and how the entry might be adjusted.

That said, the matter is not as clear cut as you suggest. While the term “atheism” is used in a variety of ways in general discourse, our entry is on its meaning in the philosophical literature. Traditionally speaking, the definition in our entry—that ‘atheism’ means the denial of the existence of God—is correct in the philosophical literature. Some now refer to this standard meaning as “positive atheism” and contrast it with the broader notion of atheism” which has the meaning you suggest—that ‘atheism’ simply means not-theist.

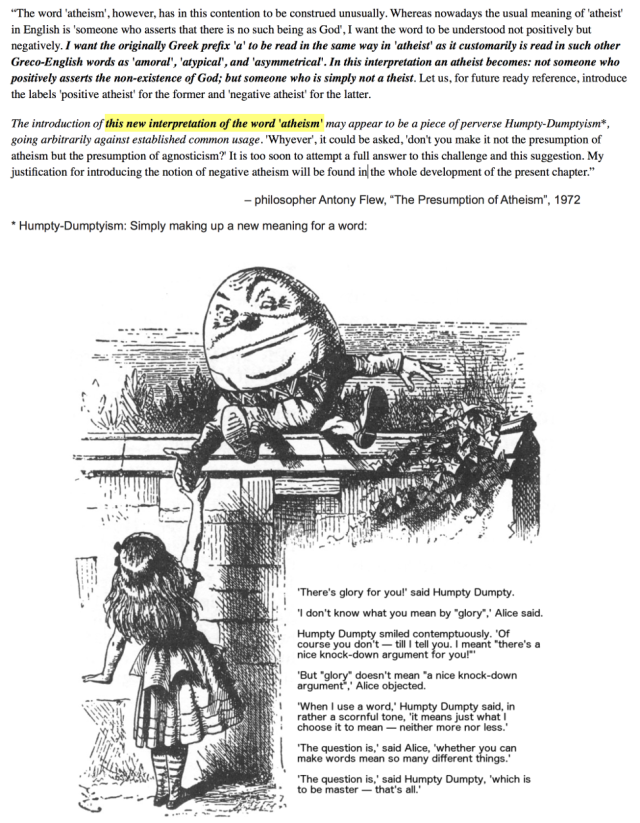

In our understanding, the argument for this broader notion was introduced into the philosophical literature by Antony Flew in “The Presumption of Atheism” (1972). In that work, he noted that he was using an etymological argument to try to convince people *not* to follow the *standard meaning* of the term. His goal was to reframe the debate about the existence of God and to re-brand “atheism” as a default position.

Not everyone has been convinced to use the term in Flew’s way simply on the force of his argument. For some, who consider themselves atheists in the traditional sense, Flew’s efforts seemed to be an attempt to water down a perfectly good concept. For others, who consider themselves agnostics in the traditional sense, Flew’s efforts seemed to be an attempt to re-label them “atheists”—a term they rejected.

All that said, we are continuing to examine the situation regarding the definitions as presented in this entry.

All the best,

Yours,

Uri

——————————————————-

Uri Nodelman Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Senior Editor

CSLI/Cordura Hall editors@plato.stanford.edu

Stanford University ph. 650-723-0488

Stanford, CA 94305-4115 fx. 650-725-2166

——————————————————-

[EVE NOTE: Emphasis mine.]

[EVE NOTE: You also have to admit that “Based on a false etymology of a word, one grammatically plausible but as it happens, etymologically incorrect in the word’s history, I argue that we should give an established term a totally new definition, because doing so would have the advantage of making the position that I happen to hold (in 1972—I’ll change my mind later) a distinct rhetorical (but not substantive) advantage in arguments and debate about the subject.” If this is not special pleading, there is no such thing as special pleading.]

Many people are mistaken about the etymology of the word “atheism.” They think it comes from an alpha-privative negation a- joined with theism, that is, they think

atheism = a- theism

or

atheism = the negation of theism

That is not where atheism comes from, however. ‘Atheism’ is in fact an older word than ‘theism.’ It comes originally from the Greek ἄθεος meaning ‘godless’ or ‘without god’. The -ισμός is a later addition, which means “doctrine of” or “teaching of.” Hence

atheism = ἄθεος -ισμός = atheos -ism

or

atheism = the doctrine or teaching of Godlessness, i.e. the teaching that there is no God.

Here’s a breakdown of the history:

As noted above the new redefinition of atheism as “lack of belief in God” was a bit of philosophical slight of hand (or more precisely slight of language, or even more precisely sophistry, perpetrated Antony Flew and a few of his atheistic fellow travelers starting in the early 1970s. Flew was probably the most consistent atheist apologist in philosophy through most of the 20th century—and it is worthwhile to note that late in his life, when retired and finally with enough leisure to read Aristotle carefully for the first time, Flew was rationally forced to reverse his lifelong position and embrace rational theism. Maybe he should have read Aristotle earlier in his career? Kudos to Flew for having the intellectual and philosophical integrity to publicly reverse himself on the very position he had built his entire philosophical career maintaining. That extraordinary act of philosophical courage and integrity almost makes me forgive him for perpetrating this pernicious bit of sophistry:

ADDENDUM: I’m not making this up. Of course I’m not, because I don’t just make stuff up. But for those atheists reading this who just assume that I am making it up, here’s a link to what the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has to say about it, in response to atheists’ persistent attempts to bully them into changing their definition:

Atheists vs The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Hint: They say the same thing I do. The “redefinition” of atheism was an argument strategy by Antony Flew, one which was never accepted as any sort of consensus, and one for which there are excellent reasons to reject.

I recently made a post to Twitter to explain why the simplest kind of moral subjectivism necessarily collapses into emotivism or moral non-cognitivism. The basic argument is that one cannot coherently reduce “P is wrong” to a mere opinion or belief that “P is wrong” because, opinions and beliefs are propositional attitudes towards a proposition, in this case, the proposition “P is wrong,” which, if it is proposition, must necessarily have a truth-value. If it does not have a truth value, it is senseless to claim that the analysis of such judgements is to say that someone has a view about what its truth value is.

This point is made very cogently by philosopher David S. Oderberg in his magisterial Moral Theory: A Nonconsequentialist Approach, which I highly recommend to all my readers, as well as its companion volume Applied Ethics: A Nonconsequentialist Approach.

I here reproduce Oderberg’s analysis from Chapter 1 of his book, specially about the semantic objection to moral relativism—a case originally made by philosopher Peter Geach, whose work I also highly recommend to anyone interested:

______________________________________________________________

Perhaps the most widespread form of relativism, again deriving from the philosophy of David Hume, is what I shall call personal relativism, more usually called subjectivism. The central claim of personal relativism is that the truth or falsity (truth value) of moral statements varies from person to person, since morality is merely a matter of opinion. Now there are various ways in which subjectivists have elaborated this basic thought, developing more or less sophisticated semantic theories linking moral judgements with statements of opinion. It is impossible to look at them all, but since the sorts of objection I will raise can be applied in modified form to different versions, let us take just one kind of subjectivist theory. It is one of the more simple varieties, and while many philosophers would say it was too simple, it also happens to be the sort of subjectivism that the vast majority of students of moral philosophy believe; and it is an approach that many will continue to believe even after they have finished studying philosophy!

According to this version of subjectivism, there is no objective truth to the statement, for instance, ‘Child abuse is wrong’: all that a person is entitled to claim is something equivalent to ‘I disapprove of child abuse.’ Instead of saying ‘I disapprove of child abuse’, Alan may say ‘Child abuse is wrong for me’, or ‘Child abuse is wrong from my subjective viewpoint’, but he is not then allowed to say ‘Child abuse is wrong, pure and simple’, since it might be right from Brian’s subjective viewpoint—he will say ‘Child abuse is right for me, though it is wrong for Alan, who personally disapproves of it.’ Generally speaking, moral judgements can never be considered apart from the question of who makes them. A moral judgement, ‘X is wrong’, made by a person P, can only be assessed for truth or falsity by relativizing it to P: the subjectivist says that ‘X is wrong’, uttered by P, is equivalent in meaning to ‘I disapprove of X’ uttered by P. If an observer were to report on P’s opinion, he would say, ‘X is wrong for P, or as far as P in concerned; in other words, P disapproves of it.’ But the observer can still say, ‘However, I personally approve of it, so “X is wrong” is not true for me.’

For the subjectivist, to claim that there is a fact about the morality of child abuse, which transcends mere personal opinion, is a philosophical mistake. Certainly, there are facts about what is wrong for Alan, right for Brian, and so on. These facts are genuine—they are reports of the opinions (or ‘sentiments’ to use Hume’s term) of individual moral judges—but since each judge makes law only for himself, he cannot impose his view of things on others. For the subjectivist, once the facts are in concerning the moral opinions of those engaged in a disagreement, there is no room for further argument. More accurately, there might be room for argument over other facts: Alan might claim ‘I approve of child abuse’ because he does not know the psychological damage it does to children. Had he known, he would have claimed ‘I disapprove of child abuse.’; and another person might change Alan’s mind by pointing out the relevant facts. But what the personal relativist holds is that as long as there is no dispute over the facts, two people can make opposing claims about the morality of a certain action or type of behavior with no room left for rational dispute. That have, as it were, reached bedrock.

As was said, the version of subjectivism just outlined is a simple one and all sorts of refinements can be added. Still, it is the view held by very many philosophy students, not to say quite a few philosophers (and certainly vast numbers of the general population), and should be assessed in that light. Further, as was also noted, the general kinds of observations that can be raised against it apply to the more sophisticated versions. We can only consider a few devastating objections here, but it should be noted that the validity of any one on its own is enough to refute subjectivism, whatever the strength of the others. Given the weight of all the objections, however, it is surprising that personal relativism is so widely held.

First there is the semantic problem: A proposition of the form ‘Doing X is wrong’ uttered by P (for some action or type of behavior X and some person P) is, according to the personal relativist, supposed to mean no more nor less than ‘P disapproves of doing X’: the latter statement is claimed to give the meaning or analysis of the former. But ‘P disapproves of doing X’ cannot, on this analysis, be equivalent to ‘P believes that doing X is wrong’, since ‘Doing X is wrong’ is precisely what the relativist seeks to give the meaning of; in which case the analysis would be circular. On the other hand, the relativist might again analyze the embedded sentence ‘Doing X is wrong’ in ‘P believes that doing X is wrong’ as ‘P believes that doing X is wrong’, and so on, for every embedded occurrence of ‘Doing X is wrong’, thus ending up with an infinite regress: ‘P believes that P believes that P believes . . . that doing X is wrong.’ This, of course, would he no analysis at all, being both infinite and leaving a proposition of the form ‘Doing X is wrong’ unanalyzed at every stage.

Such an obvious difficulty might make one wonder that any relativist should support such a way of trying to analyze ‘Doing X is wrong’; but if he is committed to the idea that morality is a matter of opinion or personal belief, it seems that he tacitly invokes just such a pseudo-analysis. The only other route the relativist can take is to assert that ‘P disapproves of doing X’ needs no further gloss: it is a brute statement of disapproval that does not itself invoke the concept of wrongness (or rightness, goodness and the like). But then personal relativism collapses into emotivism, the theory that moral statements are just expressions of feeling or emotion and only appear to have the form of judgements that can he true or false. Emotivism is a different theory from relativism, however, and more will he said about it in the next section. Unless the personal relativist can give an analysis of disapproval that is neither circular, nor infinitely regressive, nor collapses his theory into emotivism, he is in severe difficulty; and it is hard to see just what such an analysis would look like.

David S. Oderberg, Moral Theory: A Nonconsequentialist Approach; Blackwell: Oxford, 2000; pp. 16-18.

________________________________________________________________

In case it adds something, I will also append the write-up I made for Twitter:

As you know, the Image of the Cave, which is the centerpiece of Plato’s Politeia (or Republic) is an image of human nature in chains and the story of an escape—a healing, Socrates says—from our default condition, which is one of bondage and ignorance.

There are people, though, who think that healing is what we need to be healed from, and anywhere outside the prison is what needs to be escaped. In a quite literally Orwellian “freedom is slavery” argument, I have been told that only they are truly free who are slaves, and that free men and women are enslaved—by their freedom.

This is one of those times that I will choose Socrates’ simplemindedness over the sophisticated sophistry of the sophists—I’ll go with the freedom of the mind that’s just freedom, not the sophistical freedom that is the “true freedom” of mental slavery.

But let’s take a look at this idiocy, shall we? It’s meant to “cure” me of Platonism, and since Platonism is, at bottom, the belief that reality exists and can be known, it is meant to cure me of these beliefs too. Let’s see if it succeeds, shall we?

Nine whole points. Let’s take them one at a time, shall we?

1. Plato’s essentialist, historicist and degenerative Theory of Forms or Ideas is a bad idea.

1. This is nothing more than name-calling. And it isn’t even accurate name-calling. Platonism is as anti-historicist as one can get, since to be a Platonist is to hold that there are entities and intelligible structures in reality that do not vary over time—things like mathematics or the laws of nature. It is the Caveman (as I shall call him) who is the historicist, as we will see, and who holds that human thought is incapable of rising above its historical situatedness. As for “degenerative,” the word holds no meaning here. Again, Platonism holds that there are entities and structures within reality that do not change, and being changeless, cannot degenerate. If the Cavemen is asserting there is something “degenerate” about Platonism itself, he hasn’t said what it is or even might be, so that claim can be ignored.

2. Nothing — mind, matter, self, or world — has an intrinsic or real nature.

2. Pure self-contradiction. Supposing it were true, it would be the nature of all these things not to have a nature. To be able to assert this, one would have to know that being or reality is this way—but what is being denied even as it is being asserted is that there is a way reality is. And “there is no way reality is” is just as self-contradictory an assertion as the assertion “there is no truth” (a proposition the Caveman also accepts, as we will see).

3. That does not mean that the world does not exist. The world is independent of our mental states.

3. Flat contradiction of 2. Caveman now states, in opposition to his self-contradictory principle 2, that the world does indeed have a nature, and that that nature is “to exist independently of our mental states.” Remember he said this, because his right to say this is going to be an issue.

4. It means that truth, knowledge and facts cannot exist independently of the human mind. Truth, knowledge and facts are properties of sentences, which make up larger theories and descriptions.

4. Idiotic on several levels. I am certainly willing to concede that knowledge cannot exist apart from some mind (it doesn’t have to be a human mind)—since knowledge JUST IS the apprehension of some true proposition by some mind. Notice however that Caveman in the next sentence will ridiculously ascribe knowledge not to minds, but to sentences. No, Caveman, sentences do not KNOW THINGS.

[Philosophy 101 lesson: Following the principle of charity, I’m going to take Caveman’s “sentences” to mean “propositions,” although strictly speaking he is confused. Propositions are the primary truth-bearing logical entities, and they relate to sentences in that they are expressed by sentences. Using the standard philosophical example, consider two sentences: “Snow is white” and “Schnee ist weiss”. The sentences are different. One is an English sentence and one a German sentence. The can be found in different locations on your computer screen. If they were spoken, they would be spoken at some time, in some place, by some speaker, etc. However, they both express the same proposition, which is the logical expression of the relation between a real entity, snow, and a real property of that entity, being white. That snow is white is a state of affairs in the world or a fact. The relation of snow to whiteness is an intelligible proposition which is true (the fact that snow is white makes the proposition ‘snow is white’ true). Propositions are universal. Sentences are particular. When you are I or anyone comes to know ‘snow is white’, we have the same propositional attitude towards the very same proposition, viz. that snow is white. If this were not so, we would not all know the same fact or truth about snow, but we would each ‘know’ an individual fact or truth relative to us—but the nature of knowledge is such that it is common to all. And once we have propositional knowledge we can express these propositions that we know in the linguistic entities called sentences. And it is irrelevant whether we do this by means of English, or German, or Chinese.]

As I’ve just mentioned, facts are best construed as the truth-makers of true propositions. This is because facts, as states of affairs, exist independently of their being known, that is, independently of human minds—contrary to Caveman’s assertions. It should be a fairly trivial point to note that IF Caveman is correct, we human beings produce not only the entities that may or may not be true, affirmative sentences or negations, BUT ALSO produce the truth-makers of these things, this makes FACTS and TRUTH things that are produced by human beings. We would, in this case, not only be the ones who produce claims about reality, but we would produce/create/manufacture the truth-makers that make our claims true. And this means that we human beings have the power to make any claim about anything true or false by our creative wills. Hello Nietzsche, my old friend. It’s good to meet with you again.

Finally, Caveman’s claim that truth is a property of sentences, which I will charitably take to mean “truth is a property of propositions”, is a half-truth. There is a very important way in which propositions are the most common locus of truth—for us, since we are essentially discursive creatures or creatures of λόγος. But this is not the most primordial sense of truth—discursive truth is itself always grounded in a deeper openness of reality to comprehension that makes discursive truth possible. To put it very simply: we could not grasp or express discursive, propositional truths of the form “S is P” if S and P and their relation where not already given to us in such a way that we could grasp them in their belonging-together and thus come to know them precisely in this belonging together.

So even where Caveman gets close to saying something true, that “truth is a property of propositions,” he’s right only with a series of necessary qualifications.

5. The world can cause us to hold certain beliefs. However, neither the world nor some notion of unchanging Forms decides which description of the world is true. The world does not speak or provide descriptions. Human beings do.

5. Okay, I have decided that this is not a true description of reality.

See the problem?

The problem is an equivocation on the verb “decide.” In one sense, as creatures capable of knowing or believing, it is up to human beings to ‘decide’ what to believe. On the other hand, the way that reality is is not a matter up to human ‘decision.’ Reality is the way it is, regardless of whether human beings ‘decide’ otherwise. If Caveman seriously disagrees with this, I have a simple challenge for him: I challenge him to ingest a large quantity of cyanide and ‘decide’ that cyanide is non-toxic to human beings. If reality is controlled by human decision, he should not have a problem doing this and not dying. I maintain “Cyanide is a lethal poison to human beings” is a true description of the world. I further maintain than no amount of human “description” can change this fact.

We can do another thought experiment to bring this home: suppose that the earth became unstable for some reason and was soon to explode, much like Superman’s home planet Krypton. Suppose also that (for some odd reason) Caveman was the one who was tasked to find a solution to the imminent explosion of the earth. His solution is “Because the world does not decide what is or is not true, it is not true that ‘the earth is going to explode’. Nor can anything in the world ‘decide’ whether the earth does explode. These things—’facts’ or ‘truths’ or ‘knowledge’—are all contingent on human description. So all we need to do, as human beings, is to describe the earth as ‘not going to explode’ and it will become true that the earth is not going to explode.” Do you think that would work? I think *KABOOM*.

If human ‘decision’ could alter reality by means of ‘description,’ why would we not redescribed reality into some kind of ideal state for human beings? Why do we not live in a perfect world, if it is entirely within our power to create reality as we see fit by description?

Oh, wait, I think I know! It’s because this is bullshit, and we can’t actually change reality by redescrbiing it, isn’t it? Damn. I knew this was too easy.

6. That does not mean that truth, facts and knowledge are subjective. It means that they are a product of shared vocabularies, language games, social practices, in short, forms of life which are again contingent upon and conditioned by historical, social, environmental, and cultural factors and, in the final instance, human evolutionary biology.

6. Time to cut the bullshit. This means that we cannot have knowledge of reality. THAT is what the denial of Platonism MEANS, as I’ve said. “Contingent, historical, circumstantial truth which is produced by a variety of social factors” IS NOT TRUTH.

Caveman is putting forward a theory of reality that serves as a DEFEATER for all theories of reality INCLUDING HIS OWN. If this account is TRUE, then it itself is merely a product of some historically contingent form of life, etc., etc., and “in the final instance” of human evolutionary biology. In other words, he is FIRST a SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVIST about reality, but SECOND (inconsistently) a BIOLOGICAL REDUCTIONIST.

Neither of these things is coherent, either with the other, or with itself.

Social constructionism fails because it is self-defeating; if true, it is an unwarranted theory, because as a theory (like every theory) it is a mere social construction or convention.

Biological reductionism fails because it is self-defeating; if true, it is an unwarranted theory, because as a theory (like every theory) it is merely the outcome of mindless biological forces.

Each theory provides its own defeater, because it provides a defeater for all theories.

Any theory that provides a defeater for all theories, including itself, can be immediately rejected as unwarranted and wholly irrational.

So, that’s what I’ll do.

In this case, each theory also instantiates a performative contradiction insofar as the one who puts forward the theory intends that it be taken to be a true theory about nature of reality—which means that the proponent of the theory, despite his wishes, is committing himself by the very fact of offering a theory of reality, to the view that REALITY CAN BE KNOWN, or in a word, to PLATONISM.

Nietzsche understood this: TRUTH stands or falls with PLATONISM. That is why he said things like this

And this

And this

What we can see from this is that Caveman is one of those sad specimens of the 20th and 21st centuries, a feeble Nietzschean. He thinks he is a late-Wittgensteinian, but of course he isn’t consistent in any way, nor is there anything Wittgenstein discovered that Nietzsche was not aware of.

Caveman’s problem is not (yet) the wild incoherence of Nietzsche or the late Wittgenstein. Caveman’s problem is that he sees, dimly, that his shallow Nietzscheanism cum Wittgensteinianism requires him to reject Platonism—but his isn’t actually prepared to DO THAT, since that entails giving up the idea of TRUTH once and for all.

This is sane, to an extent, insofar as the rejection of TRUTH and REALITY is tantamount to embracing the irrational void of pure nihilism—but the inconsistent attempt to embrace the nihilistic void is, if anything, worse. It merely makes one a failure on all sides, a half-and-half, a lukewarm neither-this-nor-that, a rebel when convenient, but utterly conventional when that is convenient. “Hypocrite” would be another word.

But here’s the deal Caveman: YOU DON’T GET TO RENOUNCE PLATONISM AND KEEP IT TOO.

It’s one or the other: BEING or NOTHINGNESS; PLATONISM or NIHILISM.

And lest I be accused of putting to much weight on Nietzsche’s assessment of meaning of Plato (although Nietzsche, as his arch-enemy, understood Plato better than almost any other thinker), let us add some additional testimony:

7. We communicate successfully every day, and we use knowledge successfully every day, because we share imagined (and conditioned) realities and social practices on many levels.

7. What’s amusing is that Caveman thinks our success in knowing and communicating shows that we can “do without” Platonism.

Actually, what it shows is that Platonism is true; that is, we can know things and communicate them.

At bottom, Platonism is the theory of theories, the theory we can know things. No anti-Platonism can be coherent, since it has to assert we cannot know anything to be true, and so, by its own (anti-) theory, it cannot know what it asserts as true to be true. Caveman is merely another in a long line of people trying to escape truth by asserting the “truth” that “there is no truth” or to escape knowledge by claiming to know that “nothing can be known.” Caveman fails, and all such attempts will always fail, forever and necessarily.

8. Truth, knowledge and facts can always be redescribed by changing the language game, by changing the habits of speaking, by scientific research coming up with better theories, better descriptions that pragmatically explain better, work better according to what we want to achieve.

8. This is simply the thesis of the sophists, that because we speak about reality, we can change reality by changing the way we speak. See above for why that doesn’t work.

Caveman thinks he is being bold and new. But there is nothing new here. It is the same old sophistry that philosophy, in the person of Socrates, rose up to destroy.

Platonism is the view that, not man, but reality and truth are the measure of all things. The fact than it is man who does the measuring does not change the fact that what man measures is not man’s creation, nor is it under man’s arbitrary control.

This is of course how SCIENCE operates. Human beings gain what technological power and mastery over nature they have, only insofar as they submit to the objectivity of reality. Here is Bacon, one of the founders of empirical scientific method making this point:

The postmodern rebellion against reality is, to paraphrase Sartre, a useless passion.

9. Plato’s hypothesis of truth, knowledge and facts as unchanging essences (or “The thing in itself”, in Kant’s description) — only every seen as poorly reflected images on a cave wall — is entirely optional.

9. Platonism is “optional” only so long as you are willing to regard reality, truth, and knowledge as “optional.” And it is far from clear that that is even a coherent thing to do.

Caveman keeps making assertions which have the appearance of being meant as possibly true assertions—but since he assures us repeatedly that “truth” is a kind of social fiction (or perhaps biological fiction; see Nietzsche’s remark above)—this is in vain, a useless passion.

It is not clear that it is in any way meaningful to say that everything is a fiction, an illusion, a falsehood, etc., since these very concepts of “fiction,” “illusion,” “falsehood” seem to by parasitic on the idea of truth.

And the idea of truth is ultimately the same as the truth of ideas, that is, of an intelligible reality which shows itself to the human mind in such a way that it can be known.

Caveman has failed in his attempt to persuade me to reject truth in favor of fiction, to reject philosophy in favor of sophistry.

I remain, as always, a friend of truth, a seeker of truth and a friend of wisdom.

Which is to say, a philosopher.

Which is to say, a Platonist.

Atheists frequently claim they do not believe in God due to a lack of evidence. They will tell you such things as God is “a hypothesis,” “unfalsifiable,” “not empirical,” and so forth.

And yet, almost all of these same people believe in fairies. Or at least one fairy: The Burden of Proof Fairy. They keep telling me that this fairy is sitting on my shoulder. And that the fact that she is morally obligates me to do things they desire me to do, which I never agreed to.

Now, when someone tells you that you have to obey them because there’s an invisible fairy sitting on your shoulder, which somehow magically places you under a moral obligation, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to ask them for evidence of this. And so I do.

I get the strangest answers from atheists about why the Burden of Proof Fairy exists. At least, I find them strange, because I know they wouldn’t accept any one of these as evidence of the existence of God:

“It’s obvious that the Burden of Proof Fairy exists.”

“You are stupid if you don’t believe in the Burden of Proof Fairy.”

“The Burden of Proof Fairy exists by definition.”

“Lots of authorities say that there is a Burden of Proof Fairy.”

[Addendum: a new proof of the Burden of Proof Fairy, courtesy of Josh Randolph:

“She’s just there.”]

And my favorite,

“You have to believe in the Burden of Proof Fairy—or else the You-Have-To-Believe-Everything Monster will come and get you!”

(The You-Have-To-Believe-Everything Monster is some kind of mythical monster that has the power to morally obligate you to believe everything anyone asserts without evidence—the only thing that can cancel this moral obligation is to believe in the saving power of the Burden of Proof Fairy, confess she is real and sitting on your shoulder, and accept her moral commandments. To me, this sounds like trying to sell me a made-up cure for a made-up disease, but many of them do seem to sincerely believe in both the monster and the fairy)

What’s amazing is the sheer blind faith atheists have in the Burden of Proof Fairy. It frequently gets in the way of discussions about God. Many atheists simply won’t have a discussion about God unless I will first agree to accept their faith belief in the Burden of Proof Fairy. They just cannot accept that I won’t, and they’d rather end a conversation than proceed without my credal confession that the Burden of Proof Fairy exists. I am unaware whether there are different denominations among atheists depending on variant dogmas concerning the Burden of Proof Fairy. I assume that there are, but it seems to be nearly universal atheist orthopraxis to invoke the Burden of Proof Fairy against theists.

Amazing again is the sheer indignation with which I’m met when I ask for evidence of the existence of the Burden of Proof Fairy. I swear I think most atheists would prosecute me under some kind of blasphemy law if they could for daring to question the existence of the Burden of Proof Fairy. And yet, these are the very same people who endlessly demand and command you to produce evidence that God exists.

Why are they not aware that God exists? They usually claim that there is “no evidence”—which is nonsense of course, given the couple dozen cogent metaphysical demonstrations, the experiences and testimony of literally billions of human beings, and of course the general consensus of the human race, being at least minimally aware of the divine reality as most of us are. What they really mean is “there isn’t evidence which subjectively convinces me“—which I tend to view more as problem with the me than the evidence.

Back to the Burden of Proof Fairy. She’s invisible, undetectable by any empirical or scientific means, immaterial, and alleged to have a moral power to obligate persons to obey her. And atheists absolutely, fanatically, believe in her. Or should I write Her?

If you don’t believe me, try asking an atheist for evidence that the Burden of Proof Fairy exists. You’ll be amazed at the reactions you get.

I made a guide to understanding the Burden of Proof Fairy for you all. With cartoons! Enjoy.

Abusus non tollit usum is a Latin expression, which articulates a fundamental principle, both of life in general and in law. It means “abuse does not take away use.”

This is a very obvious principle, which essentially states that we should not get rid of a good or useful thing because said thing can also be misused—since literally everything that can be used can be misused in some way.

A hammer or a screwdriver can be used to commit a murder. This is not an argument for banning hammers or screwdrivers. Words can often be misapplied; this is not an argument to stop using the word in its proper, useful application.

This principle is so obvious that it shouldn’t need to be said. But I have learned from experience that a favorite fallacy of certain ideologues is the “argument to abuse,” which goes:

Among anarchist-libertarians, it looks like this:

Among feminists it looks like

Among the Politically Correct word police it looks like

The fallacy should be obvious. It’s an argument from “some” to a conclusion about “all,” containing the hidden, self-evidently false premise that “Whatever is true of some Xs is true of all Xs.” This doesn’t work unless you can demonstrate that in all cases the thing in question is bad—but of course this is just what pointing to only some cases fails to do.

I once again apologize for insulting your intelligence with ridiculously simple graphics, but some people seem to need them:

As some of you know I have been involved in an argument on Twitter with one DrJ (@DrJ_WasTaken) concerning the usage of the term “fish.” It began when he asserted that Geoffrey Chaucer was using the word “fish” (or “fissh”) wrongly, because Chaucer includes whales under the term “fish.”

I pointed out something I took to be something very obvious, that correctness and incorrectness in word usage is conventional, and is therefore contextual and relative to the community of language speakers of which one is a part. The fact that many modern English speakers would not use the word “fish” in such a way as to include whales merely reflects a change in usage, where popular language has tended somewhat to conform to usage in science, in which whales, being mammals, would not be regarded as “fish.”

Although it is not actually clear that biologists use the word “fish” in any formal sense—”fish” is, at most, a paraphyletic classification, similar to “lizard” and “reptile.” That is to say, it based on phylogenetic ancestry, but includes a couple of arbitrary exclusions. For example, here is a chart of the paraphyletic group Reptilia:

Reptilia (green field) is a paraphyletic group comprising all amniotes (Amniota) except for two subgroups Mammalia (mammals) and Aves (birds); therefore, Reptilia is not a clade. In contrast, Amniota itself is a clade, which is a monophyletic group.

In other words, “reptiles” seem to be defined as “all animals which are descended from the Amniota, with the (semi-)arbitrary exclusion of mammals and birds.”

There was once a Class Pisces, but this is no longer recognized as a valid biological class. Nowadays, the biological use of “fish” seems to refer to three classes: Superclass Agnatha (jawless “fish”; e.g. lampreys and hagfish), Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous “fish”; e.g. rays, sharks, skates, chimaeras), and Class Osteichthyes (bony “fish”), but excluding Class Amphibia, Class Sauropsida, and Class Synapsida, although these all belong to the same clade. So “fish”, like “reptile” is a paraphyletic classification. It includes some members of a clade but just leaves some other members out. Here’s a chart:

I think this element of arbitrariness in the biological taxonomic classification of fish is important, and goes to substantiating my point about the flexibility of the usage of the word “fish.” In this case, the point is: the term “fish” even as used in contemporary biology is essentially arbitrary. It involves drawing a line around certain kinds of living beings and saying “These are fish.”

The issue is that DrJ holds the position that, for any given English word, such as “fish,” there is one and only one absolutely correct usage of this word, that this correct usage is completely independent both of all historical context and of actual usage, and that any other usage of the word is, in some absolute way, INCORRECT or WRONG.

Thus, he maintains, that English speakers in Chaucer’s day, including Chaucer, were using the word “fish” wrongly, because they do not use it as modern scientists use it, which is the one, single, eternally correct way—even though, as I mention above, this modern “scientific” usage is essentially an arbitrary paraphyletic grouping.

This position generates what I take to be a number of absurdities, more than sufficient to refute the position by a reductio ad absurdum. For example, it entails that in many cases, and definitely in the case of the word “fish,” whatever English speakers first coined the word “fish,” used the word they had created WRONGLY, the very instant they used it at all. They had just now made a new word to name something, but they were ignorant of the fact that the word which they had just now created, really names something else—their intentions in creating the word notwithstanding.

Now, there are many natural facts about animals, e.g. that whales give live birth and so are mammals. But “the correct name of this animal or animal kind in English” is not a natural fact. I would have said that it is a social fact or a convention (which still seems correct to me). But DrJ denies this. He maintains that there are facts about the correctness of word usage which are neither natural facts nor conventions.

As a Platonist, I am perfectly prepared to admit that there are such facts, non-natural facts, for example, facts of logic or mathematics. Logical facts and mathematical facts are neither natural or physical, because they are about things which are immaterial, nor are they conventional or social, since they are entirely objective. I would not, however, have thought that English word meanings were the sorts of things about which there could be transcendent metaphysical facts outside time and space, not subject to the actual usage and conventions of English speakers. I had always taken it to be obvious that word usage was a convention or social fact.

I have spoken of DrJ’s belief in PLATONIC WORD-MEANING HEAVEN. I intended this term to show (what I take to be) the absurdity of his position, but I want to stress that it is LOGICALLY NECESSARY that he believe in something like this. If the CORRECT meaning of words is determined neither by nature nor by convention, it MUST necessarily have some kind of eternal, transcendent ground beyond convention and outside of nature—if not God, then at least something like Platonic Word-Meaning Heaven. I don’t care what he calls this transcendent ground beyond nature which determines eternal correct word meaning—all that matters to me is that he must believe in such a thing, because whatever it is (and perhaps he knows the one, true, eternally correct name for it?), this is what he is appealing to when he holds there is a standard of correctness for words which is non-conventional and above nature. He cannot be, for example, appealing to the usage of modern biologists, because his claim JUST IS that this usage is eternally correct, and—he has been very clear on this point—it was correct in Chaucer’s day, before any actual English speaker used the word “fish” in this way—which is what enables him to say that Chaucer’s use of “fish” is incorrect, and that the use of “fish” by whichever English speakers who first used the word “fish” was equally incorrect.

We are not debating about HOW the word “fish” is used by modern biologists (although that might be interesting—it’s paraphyletic nature seems to add an ad hoc, arbitrary element, which makes his case that it is the one, true, eternally correct use even more suspect.)—we are discussing the grounds of DrJ’s claim that ONLY the use of the word “fish” by modern biologists is or can be CORRECT, and that any and all other uses, past, present, or future, are, necessarily, INCORRECT or WRONG. It is very clear DrJ is maintaining that correctness in word-usage is in some way an eternal truth comparable to the truths of mathematics and logic. I remain unconvinced by this claim, and have yet to see any good evidence offered for it, beyond a dogmatic insistence that it is so, ad nauseam. But I want to know what his actual arguments are for this Platonic position on word-usage. I am a Platonist, so he’s already got my concession that there are such things as eternal, non-physical, not-temporal standards (e.g. of math, logic, ethics, etc.). I’m just not convinced that word usage is like that. Given the way that words vary among languages and the way they change meaning over time, it seems absurd to me to class word-meanings among the eternal objects—although of course we are forced to speak of eternal entities by means of temporal words, but that’s another story.

My suspicion is that he is continually confusing the USAGE OF A WORD TO REFER to some truth about the world with the REFERENT BEING REFERRED TO IN THE USAGE. That is to say, I think he is doing the equivalent of confusing the natural fact that snow is white with the English sentence “snow is white.” The fact of the color of snow is what it is, regardless of how that fact is EXPRESSED in English. The very same fact can be expressed in German as “Schnee ist weiss.” But the WORDS USAGE which expresses the fact is CONVENTIONAL. Nothing in the fact of snow’s being white in any way entails that the stuff has to be called “snow” or the color called “white.” These are arbitrary sounds that convention has linked with the frozen precipitate that falls from the sky and the color or tint which is a quality of said precipitate.

Plato’s Cratylus is devoted to the question of whether or not there are “true names” for things, or whether names are conventional. Cratylus says there are true names, and Hermogenes holds they are conventional. For SOME MAD REASON the two call upon Socrates to decide the matter—Socrates then proceeds to refute Cratylus and argues him into conceding that words are conventional, and before Hermogenes has time to gloat, Socrates turns on him, refutes him, and argues him into the position that there are true names for things. And with the opponents having switched sides, and the question still unanswered, Socrates leaves. RULE OF LIFE: DO NOT ASK SOCRATES TO “SETTLE” AN ARGUMENT.

Anyway, I have a number of questions for DrJ that still remain unanswered, to wit:

1. What are the reasons for your belief in a transcendent ground which determines CORRECT word usage over and above actual historical usage? Can you demonstrate that such a Platonic realm of word meanings exists? Or that there are transcendent facts about word meaning in the same way or in a similar way that there are transcendent truths about mathematical entities and logical entities?

2. How do you access this transcendent place wherein the one true eternal correct word meanings of English are stored? I would like to know the true, eternally correct meanings of words, so I can use them properly. How do I check which definition is the one, true, eternally correct one? What sort of argument would demonstrate that usage X of a word is the ‘one, true, eternally correct’ one and usage Y is not?

3. If your thesis is true, why don’t linguists, who study language, recognize that it is true? Or if any linguists do maintain that there is one and only one eternally correct usage for any given English word, can you please give me their names? And can you point me to their arguments as to why they think this is true?

4. If your thesis is true, why don’t lexicographers recognize it to be true? Why do dictionaries, at least every one I am familiar with, give more than one definition for some words? Are lexicographers unaware that there is and can be only one true correct meaning for each word? For example, the Oxford English Dictionary says of itself

The OED is not just a very large dictionary: it is also a historical dictionary, the most complete record of the English language ever assembled. It traces a word from its beginnings (which may be in Old or Middle English) to the present, showing the varied and changing ways in which it has been used and illustrating the changes with quotations which add to the historical and linguistic record. This can mean that the first sense shown is long obsolete, and that the modern use falls much later in the entry.

Why does the OED focus on “the varied and changing ways in which [a word] has been used” instead of on the “one, true, eternally correct meaning” of a word? Shouldn’t the one, true, correct meaning be regarded as more important than all the historically incorrect usages? Why does the OED speak as if multiple senses of one word are all valid, if this is (as you say) false? Or again, the OED says

What’s the difference between the OED and Oxford Dictionaries?

The OED and the dictionaries in ODO are themselves very different. While ODO focuses on the current language and practical usage, the OED shows how words and meanings have changed over time.

Why does the OED think that word meanings change over time, when they are, in fact, static and fixed by your transcendent standard of correctness? Why do all dictionaries think this? Why have you not corrected the OED and the various other dictionaries on this extremely important point? Surely, if it is worth taking the time to explain to me on Twitter that words have only one, true, eternally correct meaning, it is worth explaining this to the OED and other dictionaries, so they can change their priorities. Or can you point me to a dictionary whose policy is to give ONLY the one, true, eternally correct definition of each word?

5. If every English word has one, true, eternally correct meaning, does this go in reverse? Does every eternal meaning have only one true word to which in corresponds? Or do you hold that although there is only one, true, eternally correct meaning for each word, there can be arbitrarily many words (e.g. in other languages) that express this meaning? In other words, is “fish” the one, true, eternally correct word to express the one, true eternally correct meaning of “fish,” so that all other languages are wrong to not use the English word “fish”? Is Chaucer’s “fissh” wrong? Is the German “Fisch” wrong? Are they “less wrong” than the French “poisson”? Is it always English words that are correct, so that all speakers of non-English languages are always using all words wrongly, just because they are not speaking the one, true, eternally correct language, English? Or are the true, eternally correct words divided among the various languages of the world?

It brief:

Definitions depend on usage. For example, anyone is free to stipulate the definition of any word. One could, if one wanted to, define feminism as ‘the doctrine that women are fundamentally inferior to men and should serve them.’ This would certainly create an odd sort of ‘feminist,’ which is the main reason we try not to do that with important words. Definitions are meant to make something clear. Dictionary definitions are meant to make clear how a given word or term is actually used or has been used in a given language.

There are of course many dictionaries, and thus many “dictionary definitions” of feminism (and everything else), but this is the go-to one used in most public discourse on the internet, the one given by Google when you type “define feminism” into it:

Definition is something people do for a reason. It is an action that has an end, namely, to make clear the meaning or usage of the term being defined. It is thus possible to fail in giving a definition, by failing to capture the actual usage of a term. And like other human activities that aim at a definite end, definition has rules or guidelines; these rules are not compulsory rules, in the sense that “you morally ought to obey them,” but are similar to logical rules, in the sense that “if you violate these rules you will fail at your task”—whether that task be “making a valid argument” or “making a term clear in its usage.”

Briefly, the criteria of sound definition are

I grant that, as far as I can see, the “dictionary definition” of feminism meets criteria 3-6.

Where it fails are 1 and 2.

The first point is fairly clear, and it is why most people get very annoyed when feminists appeal to the dictionary definition of feminism. It is annoying because they are very clearly NOT trying to explain what feminism IS, but trying to SELL IT to you by creating a false equivalence with something that sounds (and is) much better than feminism, viz. egalitarianism, as applied to the sexes.

This point is so stupidly simple, it can be put in the form of a diagram that even a child can understand. I apologize for insulting your intelligence, but it really IS necessary to hammer this point home with this lack of subtlety—because the people who cite the dictionary definition aren’t even trying to be honest, it is necessary to rub their faces in how wrong they are:

This is the basic problem. The sets of “feminists” and “people who advocate for women’s rights on the basis of social, political, and economic equality with men” are just not coextensive. Yes, they overlap somewhat, but there are very many feminists who do not advocate for equality, and very many people who do advocate for the equality of the sexes (and I am one of them) who are not feminists. And the reason that so many of us advocates of women’s equality are NOT feminists, is precisely because so many feminists are NOT advocates of equality.

Since feminism (femin-ISM) is an ideology, and ideologies are belief-systems, no one can force anyone else to subscribe to an ideology against their will. And yet, this is what those who cite the dictionary definition of feminism are trying to do: they are trying to FORCE you to self-identify as a feminist, on the basis of some of your beliefs, and they are trying to do it with a FALSE definition of feminism. And one thing that is, or at least should be, anathema in a pluralistic liberal democracy is attempts to FORCE others to believe as you want them to believe. In a free and democratic society, we use PERSUASION rather than FORCE, and ideally, RATIONAL PERSUASION, which is different from COERCIVE PERSUASION and MANIPULATIVE PERSUASION.

To be clear, I was using “force you to identify as a feminists” in the looser sense of “coercively and manipulatively persuade you to.” There have only been a few attempts to use genuine force (so far), as when a member of the E.U. Parliament attempted to make it a CRIME to criticize feminism. And of course, governmental FORCE was what Anita Sarkeesian and Zoe Quinn were asking for when they went before the UN, asking that the UN put pressure on national governments to implement feminist ideology by law. However benighted and ridiculous Emma Watson’s HeForShe campaign was, at least she wasn’t advocating that the UN take steps to see her ideology implemented by force of law.

So, while most feminists would LOVE to use actual FORCE to punish anyone who dissents from their ideology, they usually don’t have the power to do this, except in limited areas. Rejecting feminism will indeed get you fired as a matter of course at many colleges and universities in the United States, where feminist ideologues essentially control those institutions.

But let me explain why this is DISHONEST PERSUASION: it is (1) COERCIVE PERSUASION in the sense that feminists will do whatever is in their power to harm you if you do not agree with them, and it is (2) MANIPULATIVE PERSUASION in the sense that feminists deliberately distort the truth in order to sell and push their ideology. The basic move in the appeal to the dictionary definition is an appeal to shame. In a highly egalitarian society such as ours, people are very vulnerable to being socially shamed if they hold anti-egalitarian views. Feminists, by simply equating feminism with the egalitarian view in regard to the sexes, attempt to socially shame and stigmatize anyone who does not identify as a feminist or accept feminist ideology as being an anti-egalitarian or sexist.

This tactic is of course not limited to appeals to the dictionary; many feminists as a matter of course label anyone who disagrees with their ideological position as “sexist” or even “misogynist.” This is DISHONEST because it isn’t true. Most people in the modern West are egalitarians with respect to the sexes—ironically, the largest group in the modern West of non-egalitarians with regard to the sexes are certain kinds of feminists, who are female supremacists. So, a feminist tells a LIE (manipulative persuasion) by saying feminism and egalitarianism of the sexes are the same, and attempts on the basis of this lie to SHAME and STIGMATIZE you (coercive persuasion) for not being a feminist on the false basis that not being a feminist is equivalent to not being an egalitarian regarding the sexes, or worse, is being a sexist, or still worse, is being a misogynist.

All this seems pretty obvious. I’m only bothering to spell it out because I enjoy laying things out clearly.

The SECOND reason the dictionary definition of feminism fails is that it is not unambiguous. The problem turns on the word “equality.” As the philosopher Roger Scruton has observed, there is hardly a more important word in modern political discourse that is so entirely resistant to clear definition:

Almost everyone in the modern West is “for equality,” but at the same time is completely unable to say what it is, how we would get it, and why it’s so desirable in the first place. Almost no one, in the West or anywhere else, thinks that people should be treated “equally” in every respect. Nor is it clear exactly what it even MEANS to “treat people equally” in many cases.

Which brings us back to the problem with using such an unclear term in a definition. There are simply too many ways to take “equality” for the definition to actually make clear what it is talking about. Let me give just two examples of why this is bad:

(1) Since one kind of equality is identity or sameness, a stupid person who desires “equality” will tend to desire what we could call exactly-the-same-ness. The problem with this is the context of the sexes, is that men and women are NOT the same, but rather different in fundamental ways. This doesn’t mean, of course, that they should be treated unequally in the sense of unfairly, but remember, this is the stupid person’s reasoning we are going through. “The only way to achieve equality is by sameness,” the stupid person reasons, “so equality requires that men and women be treated the same, and even more, that they be made the same. And since it is a moral imperative that they be made the same, they must really be the same, metaphysically. So we must ignore any evidence of natural difference, for example, biology, and indeed more than ignore it, condemn it as sexist.”

Since stupid people tend to equate equality with sameness, they also tend to equate difference with inequality, and so a great deal of modern feminism, as an ideology, advocates biological denialism. MOST PEOPLE who are principled egalitarians and want to see justice between the sexes (which is most people) are NOT signing up for an ideology that requires them to deny biology and other inconvenient parts of reality. The dictionary definition of feminism does nothing to rule out the interpretation of equality as exactly-the-same-ness, which entails biology denialism specifically and more generally reality denialism.

(2) This one is also fairly obvious, given that it has been a point of contention in the West at least since Rousseau and the French Revolution, although it is probably more associated in the popular mind with Marx and Marxism. I am of course talking about the distinction between equality of opportunity, which holds there ought to be a “level playing field” in which no one “begins the game” with any unearned or unfair advantages or disadvantages, and that, so long as the game isn’t rigged, and the players play fairly, justice has been satisfied, even if the outcomes of the players may be widely different; and equality of outcome, which holds that the game must be rigged to ensure that no one wins or loses, and indeed, no matter what the players do or fail to do, they obtain exactly the same results in the game.

The trouble with the Marxist understanding of equality is that it is antithetical to the other primary modern Western value, freedom or liberty. The classical-liberal view accepts inequality of outcome, because it values both equality and liberty. So once again, the dictionary definition of feminism fails to tell us whether a feminist is interested in preserving freedom and liberty, especially and including women’s freedom, or whether a feminist, in Marxist fashion, is an authoritarian or totalitarian who hates liberty because it results in a kind of inequality which is deemed unacceptable. Most people in the modern West place a high value on liberty, and would not sign up for an ideology that is anti-liberty. However, there is also a rather sizable and vocal feminist minority (perhaps even a majority, certainly a plurality) who are more than happy to sacrifice liberty for the sake of their (Marxist) vision of equality—most of them are delusional or catastrophically naïve, and advocate the suppression of liberty on the assumption that it will only be the liberties of others which will be restricted.

I’m sure that if Anita Sarkeesian and Zoe Quinn got the censorship laws they advocate put in place, they would expect not ever to be subject to them—but that isn’t how things work, when you give the state broad powers to censor and control. For example, consider a case from the history of feminism itself: Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin, thwarted time and again in their attempts to implement censorship laws in the United States (they were repeated blocked by the First Amendment) eventually turned their efforts to Canada, which has no equivalent of the US’s First Amendment. And they partially succeeded! It became part of Canadian law that certain kinds of books could not be imported into Canada nor sold in Canadian bookstores. Really, they should have seen it coming. Now, since the laws banned books that contain thing X, and MacKinnon and Dworkin write books about how awful a thing thing X is, it naturally follows that their books contain thing X—yes, it is there only in order to be condemned, but the law makes no distinction between various uses of thing X. So, to their surprise and horror, MacKinnon and Dworkin found that they had succeeded in banning their own books in Canada and among the most affected by the new censorship laws were feminist bookstores and publishers, who found they could no longer publish or sell feminist books thanks to the new feminist censorship law. Feminism had gotten what it had asked for, and it had succeeded in censoring itself!

In sum, the dictionary definition of feminism fails as a useful definition because it asserts something false to actual usage, namely, the identity of feminism and egalitarianism regarding the sexes—and it does this dishonestly, as a technique to coerce and manipulate by means of appeals to shame made on the basis of this conflation; furthermore, it fails to sufficiently make clear what “feminism” even means, with the result that entire point of giving a definition, to make the meaning of a word clear, is not achieved.

I could talk about some other things, such as the inherent sexism involved in term itself,

but that is more of a meta-criticism of the term “feminism” than the failure of the dictionary definition of it. So let this be enough for now.

I’ll leave you with a link to Satoshi Kanazawa’s article Why Modern Feminism is Illogical, Unnecessary, and Evil. Read it and think it over.